Art and collections

We care for one of the world's largest and most significant collections of art and heritage objects. Explore the highlights, our latest major exhibitions, curatorial research and more.

The wildly imaginative works of Beatrix Potter have entertained readers for decades. But is there more to her work than kittens in pinafores and toads in dinner jackets? At Hill Top and the Beatrix Potter Gallery in the Lake District, the National Trust looks after an extensive collection of illustrations, unpublished sketches and personal letters that reveal Beatrix’s lifelong affinity for the natural world.

Beatrix Potter was fascinated by the natural world from an early age. With her younger brother Bertram, she kept a menagerie of animals in the nursery. The children studied their pets' behaviour and Beatrix made many detailed drawings of them in a homemade sketchbook.

While Bertram was sent to boarding school, Beatrix was kept at home where she was educated by a series of governesses. She was instructed in drawing and painting and, in conjunction with trips to the Museum of Natural History, was encouraged to study and sketch animals.

Aged 15, Beatrix received her Art Student's Certificate from the Science and Art Department of the Committee of Council on Education. Although her early drawings show a certain stiffness of composition, she earned praise from the pre-Raphaelite painter Sir John Everett Millais for her skills in drawing and observation.

Each year, the Potter family (including Beatrix's pets) would pack up and move to the country, typically in Scotland or the English Lake District. These holidays provided Beatrix with an inexhaustible supply of natural objects to study and draw.

Beatrix became particularly interested in mushrooms and toadstools, and from the late 1880s to the turn of the century she produced hundreds of finely detailed and botanically correct drawings of fungi.

Her watercolour study of fly agaric demonstrates her talent for botanical illustration. The study shows the distinctive red cap with white spots and ridged underside. However, this is not a specimen drawn in isolation; Beatrix convincingly depicted the fungus in a naturalistic setting amidst ferns, ivy, beech leaves, mosses and lichen.

This naturalism did not come at the expense of imagination. For Beatrix, the countryside was also magical. As she would later show in her art, realism and fantasy could happily coexist.

– Beatrix Potter, 17 November 1896

This balance of the spirit-world and scientific knowledge, of imagination and reality is evident throughout her illustrations and story books, where an exacting observation of the natural world provides the foundation for anthropomorphic fantasy.

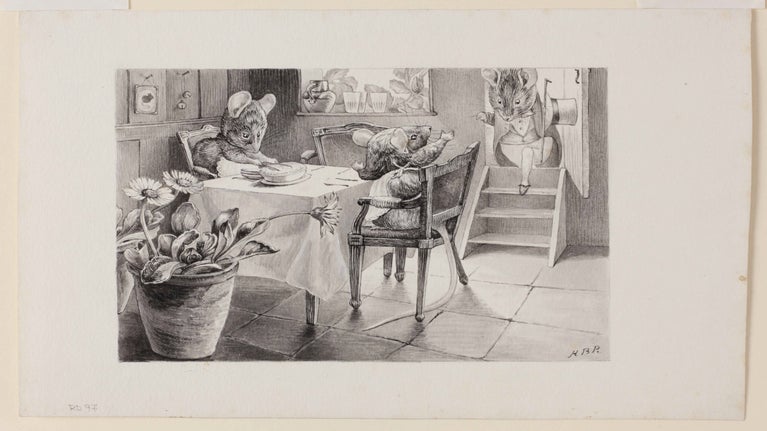

Her meticulous drawings of fungi, ferns and mosses lend themselves to an exploration of a tiny world that mirrors human life. In Dinner in Mouseland for instance, a flawlessly sketched mouse – drawn with the eye of an investigative scientist – joins his family for dinner wearing top hat and tails in a most convivial domestic scene.

As a young adult, Beatrix developed a friendship with Annie Moore, her former governess. Beatrix would visit Annie's children, often accompanied by her pet mice or rabbit; when she went on holiday, she would send them letters with amusing anecdotes.

These letters were often illustrated with sketches, recounting stories when there was no news to tell. Some of Beatrix’s earliest books originate in the stories first told and pictured in letters to the Moore children. When the eldest of the Moore children, Noel, fell ill with scarlet fever, Beatrix sent him a letter describing the adventures of a naughty rabbit named Peter.

Beatrix later had the idea of turning this story into a book, and when the story, with its black and white illustrations, was rejected by six publishers, she decided to print it privately. An edition of 250 copies was issued in December 1901 and proved so successful that a further 200 copies were issued in February 1902.

Frederick Warne & Company ultimately reconsidered and – on the condition that Beatrix provide colour illustrations – a commercial edition of The Tale of Peter Rabbit was published in October 1902. It was an immediate success, selling 50,000 copies in just over a year. Since then, it has never been out of print.

While Beatrix honed her business acumen, playing a critical role in the production and promotion of her books, she remained a steadfast observer of the physical world, amassing many studies and sketches of her natural surroundings.

These studies and sketches, many of which were made in the Lake District, formed the pictorial basis of her imaginative tales.

Beatrix first visited the Lake District at the age of 16 when her father rented Wray Castle on the shore of Lake Windermere for the family’s long summer holiday. This visit introduced Beatrix to the lakeside scenery that would become the setting and inspiration for so much of her best-loved work.

The family returned to the Lake District for their holidays in subsequent years and it was while staying at Lingholm on the shore of Derwentwater in 1901 that Beatrix was inspired with the idea for her first Lake District book, The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin.

The character of Squirrel Nutkin first appeared in a picture letter to Norah Moore in September 1901. The letter is illustrated by 12 pen and ink sketches, including one which shows a group of squirrels on little rafts sailing across a lake. That same year Beatrix filled an entire sketchbook with studies of the wooded shores of Derwentwater. These became the backgrounds for the illustrations in the book which was published in August 1903.

The area around Derwentwater became the setting for additional books and her natural history studies would continue to make appearances in her illustrations. In The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, you can identify specimen illustrations of flowers, fungi, oak apples and robin's pincushions.

In 1905, using royalties from her books, Beatrix was able to buy Hill Top, a small farm in the village of Near Sawrey in the heart of the Lake District. Beatrix once described Near Sawrey 'as nearly perfect a little place as I ever lived in'.

It was the area around Sawrey and nearby Hawkshead that would become home to so many of Beatrix’s characters and provide the setting for a total of nine of the little books.

At Hill Top, Beatrix loved the view up the garden path to the porch and front door. This view is clearly identifiable in The Tale of Tom Kitten where the illustrations give the reader glimpses of the cottage garden. Indeed, Beatrix's work on Tom Kitten coincides with periods of busy preparations in the garden at Hill Top.

When Beatrix died in December 1943 she left 4,000 acres of land to the National Trust, including 15 farms, cottages, flocks of Herdwick sheep and some areas of outstanding beauty.

We care for one of the world's largest and most significant collections of art and heritage objects. Explore the highlights, our latest major exhibitions, curatorial research and more.

Discover how Beatrix Potter’s Victorian upbringing and fascination with animals culminated in a successful career as an author and illustrator and a passion for conservation.

Visit some of the places we look after that have inspired famous writers, playwrights and poets, including the homes of Beatrix Potter, Virginia Woolf and Thomas Hardy.

Our literary-themed podcast episodes explore how several places we care for helped to shape the work of famous authors such as T.E. Lawrence, Agatha Christie and William Wordsworth.