Discover more at Carlyle’s House

Find out when Carlyle’s House is open, how to get here, the things to see and do and more.

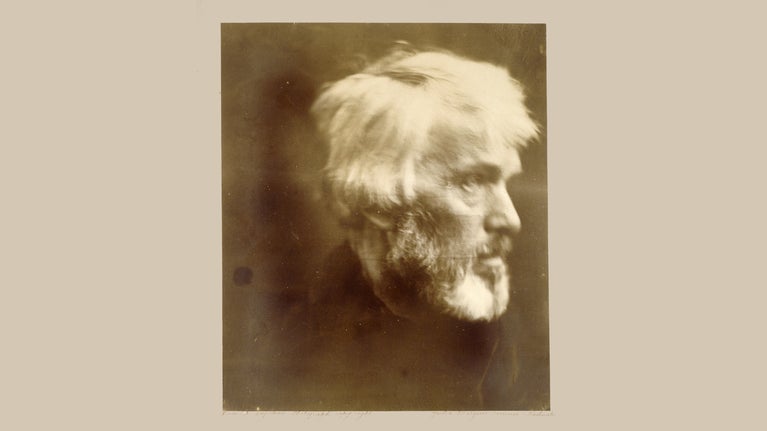

24 Cheyne Row is a terraced house and appears much like all the others on the street, but its most well-documented residents, Thomas and Jane Carlyle, make it different. Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) was one of the most famous writers of the Victorian age, and wrote many of his influential essays, history books and lectures here. Jane Carlyle (1801–66) wrote thousands of letters describing her home and the world around her. Leading artists, politicians and authors of the day visited the Carlyles in their home, where they photographed, painted and described them. Today, these artefacts, coupled with Jane’s décor and furnishings, immerse you in the Carlyles’ Victorian residence.

Built in 1708, 24 (then 5) Cheyne Row was one of ten terraced houses. Developed as one of the earliest formal residential streets in Chelsea, the three-storeyed house was built among gardens, orchards and gentry residences. Until the 1850s, the road ran straight down to the river Thames.

In 1834, husband and wife Thomas and Jane Carlyle moved to London from an isolated farmstead in rural Scotland. Thomas had no reliable income, so they searched for and rented the most affordable house they could find, for £35 a year.

By 1866, the Carlyles and their house were so recognisable that the British artist, Robert Tait exhibited his painting of the couple at home simply under the name ‘A Chelsea Interior’. The front parlour appears much the same today.

Thomas died in 1881 and within 15 years, the house opened as a memorial and literary shrine. The visitor books from 1895 onwards demonstrate the reach and continued influence of the Carlyles.

In 1834, Thomas Carlyle was an unknown writer, with no immediate prospects of a steady wage.

Over the next 3 years, Thomas wrote his breakthrough account of the French Revolution at the house on Cheyne Row. By December of 1837, he was famous.

He followed ‘The French Revolution: A History’ with lectures, essays and books describing the world he saw around him. He published the social critique ‘Chartism’ in 1839, his series of lectures ‘On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History’ in 1841 and the book ‘Past and Present’ in 1843. In ‘Chartism’, he identified the social and political changes which industrialisation was prompting across the country. Intellectuals, politicians and cultural figures across the world lauded him as a prophet and a genius with an incisive understanding of 19th-century British experience.

Anti-semitic tropes and white supremacist ideology pervaded Thomas’s work. In his essay, ‘Occasional Discourses’ (first published 1849), he used derogatory caricatures to argue for a hierarchy in which Black people should be ‘servants to the whites’ for the duration of their lives. In ‘Past and Present’ (1843), he exploited and embellished stereotypes linking Jews and avarice, and in ‘Reminiscences of my Irish Journey in 1849’, stereotypes of Irish indolence.

Thomas’s characterisation of Black people was controversial in his own time. The abolitionist Sarah Parker Remond wrote in 1866 that ‘the name of Mr. Thomas Carlyle, the literary leader of public opinion, has been for many years synonymous with all that is ungenerous and wantonly insulting to the negro race’. In 1876, Charles Darwin remembered Thomas as ‘all-powerful in impressing some grand moral truths on the minds of men. [But] his views about slavery were revolting’.

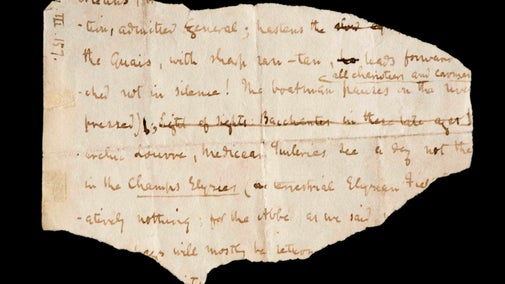

Unlike Thomas, Jane was never published, yet her letters describing the world around her make her an indispensable cultural reference for the Victorian era.

In London, Jane was at the heart of a social network of literary, political, artistic and radical figures. At the same time, she played a pivotal role supporting Thomas through his laborious research and writing process.

In their letters, Jane and Thomas describe the sights, sounds and happenings in and around their house at Cheyne Row. Their experiences centred around the house, as their place for socialising, working and living.

Thomas’s renown drew literary, scientific and political giants to Cheyne Row. Jane’s charisma and wit played a crucial role in cementing these relationships and attracting visitors. The naturalist Charles Darwin, the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray and the revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini were all early guests at the house.

The house remained a hub throughout the Carlyles’ lives, and objects in the house give insight into their social world. These include Jane’s piano, on which the composer, Frederic Chopin played; a letter from Thackeray inviting the Carlyles to tea with novelist Charlotte Bronte; and photographs of the Carlyles among friends and family.

Thomas’s last significant work, ‘Frederick the Great’ was written, in 6 volumes and with great strain, at Cheyne Row between 1853 and 1865.

Jane had orchestrated the conversion of the roof space into an attic study in 1852, attempting to create a peaceful working environment. But the ‘sound-proof study’ proved a complete failure. Jane reported in 1853 that ‘the silent room is the noisiest in the house’.

Keeping the house running was hard work, too. Jane managed at least one live-in servant throughout her life at Cheyne Row. The Carlyles lived in proximity with these ‘maids of all work’. The maid sometimes waited for hours for her chance to sleep, while Thomas smoked his pipe in the kitchen which doubled as her bedroom.

Thomas’s increasing financial security from the 1840s onwards gave the Carlyles the chance to make changes to the house and its decor. In 1843, Jane rejoiced in her success at upholstering the drawing room’s furniture ‘by my own hands!!!’ She made the curtains which still hang in the bedroom.

Jane and Thomas lived at Cheyne Row until their deaths. They adapted the house and rooms to their needs. A series of pencil sketches by the artist, Helen Allingham show the rooms as they were in 1881, filled with books, portraits and mementos.

The Carlyles’ house was a site of literary pilgrimage even in Thomas’s lifetime. Once he died, the house was re-let to new tenants and in 1894 was found by a Carlyle enthusiast to be ‘dingy and dirty ... an empty neglected house’.

Public subscriptions paid for the purchase of the house on Cheyne Row. Since 1895, it has been a museum open to the public. Visitor books record every visitor from 1895 to the mid-twentieth century.

The novelist, Virginia Woolf visited the house multiple times. Her verdict: ‘One hour spent in 5 Cheyne Row will tell us more about them [the Carlyles] and their lives than we can learn from all the biographies’.

Run initially by the Carlyle House Memorial Trust, the house was transferred to the National Trust in 1934. The National Trust has preserved what survives of the Carlyles’ mid-19th century interiors, including the hall wallpapers and Jane’s bedroom curtains. In 2018, a fundraising campaign paid for new carpets in the parlour. This completed a project to recreate the room as Robert Tait painted it in his 1865 work ‘A Chelsea Interior’.

Ashton, Rosemary. Thomas and Jane Carlyle: Portrait of a Marriage, 2002.

Thomas Carlyle - Victorian Literature - Oxford Bibliographies

Find out when Carlyle’s House is open, how to get here, the things to see and do and more.

Find out what to see at The Carlyles' House on Cheyne Row in London. Explore the original Victorian fixtures and fittings of Thomas and Jane Carlyle's home for over 40 years.

From landscape gardeners to LGBTQ+ campaigners and suffragettes to famous writers, many people have had their impact on the places we care for. Discover their stories and the lasting legacies they’ve left behind.

Learn about people from the past, discover remarkable works of art and brush up on your knowledge of architecture and gardens.

Explore the objects and works of art we care for at The Carlyles' House on the National Trust Collections website.