Lytes Cary Manor's collections

Explore the objects and works of art we care for at Lytes Cary Manor on the National Trust Collections website.

The lands of Lytes Cary Manor, Somerset, are rich in historical features extending back to Roman times. The manor belonged to the Lyte family for 500 years and evolved over the centuries to reflect their status and aspirations. In the early 20th century, the house was lovingly restored and new gardens created by Sir Walter and Lady Jenner.

Lytes Cary Manor sits on the fringe of the Somerset Levels, an area of wetland which human beings drained to create fertile farmland. There is evidence of Roman settlement close by and a Roman road, the Fosse Way, runs less than half a mile east of the house. A deserted medieval village lies under the parkland and medieval ridge and furrow plough lines are still visible in the fields.

Parts of the existing manor house go back at least to the time of William le Lyte who died in about 1316. William was a well-to-do feudal tenant, who received a grant of land in return for service to his overlord, Anselm de Gournay. The land provided him with a generous income,

The oldest visible part of the house is the chapel, completed in 1348 by William’s grandson, Peter. It began as a chantry chapel, where prayers for the souls of the family were said by a paid priest.

Over the centuries the prosperous Lyte family enlarged and enhanced the house to reflect their rising wealth and influence. The original Great Hall was probably quite a simple building, but in the 1460s Thomas Lyte (c. 1410–c. 1469) replaced it with a richly embellished chamber and adjoining private apartments.

Many of the Lytes’ eldest sons trained in the law and performed official tasks for the Crown. So when King Henry VIII planned the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, John Lyte (1498–1566) was responsible for valuing church assets in Somerset.

John extended the house to the north, south and east. To advertise his association with the king, he incorporated Henry VIII’s arms in the plaster frieze of the Great Chamber. He also introduced a number of expensive new windows adorned with heraldic shields of the extended family.

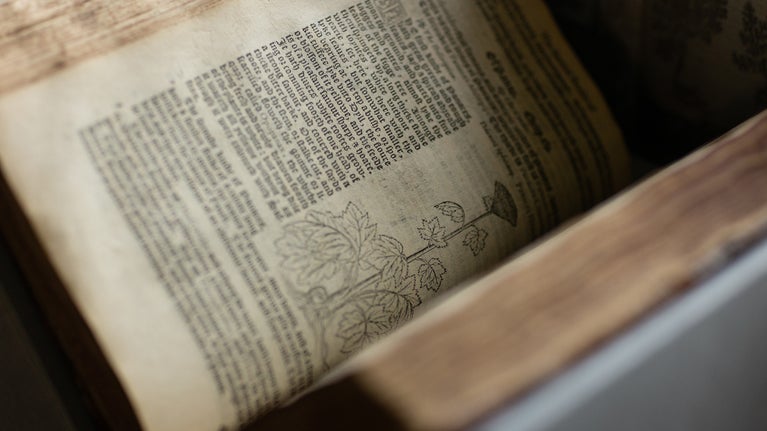

In 1558, John gave Lytes Cary to his eldest son, Henry (c. 1529–1607), a well-travelled scholar and herbalist. Henry is best known for his 1578 translation of a book about the properties of plants by the Flemish physician, Robert Dodoens. It was called A Niewe Herball and a copy is displayed in the house.

Henry’s garden was well known in his day but vanished long ago. It is likely to have contained vegetables and herbs newly introduced to England from around the world. It was also remarkable for its many types of fruit trees.

Henry Lyte and his son, another Thomas (c. 1568–1638), were both interested in genealogy, which they spiced up with make-believe. In 1588 Henry presented Queen Elizabeth I with his book, The Light of Britayne in which he fancifully traced the origins of the British to the ancient Trojans. He adopted a swan as a heraldic crest, weaving a mythical tale about swans into a fictitious family connection with Troy.

Thomas later presented King James I with an illustrated chart apparently showing the monarch’s descent from Brutus of Troy. He was rewarded for this with the fabulous Lyte Jewel, a portrait miniature of the king in a gold locket set with diamonds, now in the British Museum.

Thomas traced the Lyte family back to the 13th century and while upgrading the chapel in 1631 he had the heraldic shields of illustrious Lyte relations painted on the walls. He also added more armorial glass to the windows of the Great Hall.

The collapse of the Lyte family fortunes occurred in the time of Thomas’s great-great-grandson, whose name was also Thomas (1694–1766). In 1755, his son was forced to sell the manor to a neighboring landowner. Before long, the north range of the house was converted into a farmhouse while other parts of the building were used as stores or animal shelters and fell into disrepair. Farm buildings sprang up around it, some of which remain.

This situation continued until 1907, when Lytes Cary was purchased by Sir Walter Jenner (1860–1948) and his wife, Flora (1853–1921). Sir Walter had inherited money and a baronetcy from his father, the distinguished physician Sir William Jenner. A retired veteran of the Boer War, Sir Walter had spent most of his army career in India and was later to serve with distinction in the First World War.

Sir Walter employed the architect, C.E. Ponting, to restore the manor house and to build a new west range. Ponting followed the principles of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, which advised that architectural additions to old buildings should be sympathetic but distinguishable. Sir Walter also had new stables built for his horses. He was a keen horseman, a passion shared by his only surviving child, Esmé (1895–1932), who was briefly Master of the local hunt, the Sparkford Vale Harriers.

The layout of the present garden was mostly the work of Lady Jenner. She made a series of garden rooms in the Arts & Crafts style and stocked them with plants from Scotts Nurseries at nearby Merriott. The work at Lytes Cary paralleled what Sir Walter’s brother, Leopold, and Lady Jenner’s sister, Nora, were doing at Avebury Manor in Wiltshire. The two couples borrowed ideas from each other.

Sir Walter and Lady Jenner filled their house with pictures, curios, ceramics and 17th- and 18th-century English furniture. Much of this was procured, along with antique and reproduction panelling for the rooms, from Mr Angell of Bath. Their antiquarian taste was typical of the period, but their personal enthusiasms were reflected in equestrian pieces, army mementoes and pieces of embroidery by women of the family.

Lady Jenner died suddenly in 1921. Little over a decade later, in 1932, Esmé contracted pneumonia after a day’s hunting and died at the age of 37. To keep his beloved home and collection intact, Sir Walter bequeathed it to the National Trust in memory of himself, his wife and his daughter.

The Trust opened the main rooms in the old part of the house to the public and has kept them furnished exactly as they were in the Jenners’ time. For nearly 40 years it let the west range to Jeremy and Biddy Crittenden, who devoted themselves to further developing the garden. In 2007, the National Trust opened the west range as a holiday apartment.

Brindle, S. 2023. Architecture in Britain and Ireland 1530-1830. Yale: Yale University Press

Lowry Corry, S. R. 1881. The history of the two Ulster manors of Finagh, in the county of Tyrone, and Coole, otherwise manor Atkinson, in the county of Fermanagh, and of their owners. London: Longmans Green and Co.

Lowry Corry, S. R. 1891. The History of the Corry Family of Castlecoole. London: Longmans Green and Co.

Marson, P. 2007 Belmore: The Lowry Corrys of Castle Coole, 1646-1913. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation

Martin Robinson, J. 2012. James Wyatt: Architect to George III. Yale: Yale University Press.

Explore the objects and works of art we care for at Lytes Cary Manor on the National Trust Collections website.

Find out about exploring the manor and the objects on display inside. See a 16th-century herbal book translated into English, leather mannequins and an embroidered mirror.

Explore the garden and see the unusual shaped topiary trees and hedges or catch the light on the sundial in the orchard.

Learn about the wildlife around the estate, the carved characters and creatures to spot in the house and seasonal activities on offer.

Learn about people from the past, discover remarkable works of art and brush up on your knowledge of architecture and gardens.