Discover more at Knole

Find out when Knole is open, how to get here, the things to see and do and more.

Knole was built to impress. Over a period of 600 years, archbishops, royalty and powerful politicians commissioned some of the finest architects and craftspeople to create a vast house which would impress those approaching through the surrounding deer park. From the early 1600s, the Sackville family began filling Knole with art, furniture and textiles creating spectacular showrooms which have attracted tourists since the 18th century.

Records of a manor house named Knole date to as early as 1250. However, little is known about the structure until the nobleman James Fiennes began an ambitious building project in around 1444. Fiennes was executed for treason just a few years after buying Knole and his family sold the house to Thomas Bourchier, the Archbishop of Canterbury, for £266 13s 4d.

Sitting between the two cities at the heart of power, London and Canterbury, Knole was the ideal investment for Archbishop Bourchier in 1456. He, and the archbishops who succeeded him, were influential figures who transformed Knole into a palace for entertaining the county’s most powerful people.

Knole became a royal residence after Henry VIII admired the house while hunting with Archbishop Cranmer in 1538. His daughter, the future Mary I, lived here whilst Henry VII finalised his divorce from her mother, Catherine of Aragon. Elizabeth I visited here with her court in 1573.

Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset (1536–1608) purchased Knole in 1603. Thomas was a talented statesman, poet and playwright who had travelled widely. He brought his knowledge of European art, design and culture to Knole.

Thomas devoted the final years of his life to remodeling Knole. The work was funded by lucrative opportunities in the royal court and the vast sum he inherited from his father, who had profited from his role in dissolving the monasteries.

After Thomas’s death, Knole passed briefly to his son Robert and then to his grandson Richard Sackville (1589–1624), 3rd Earl of Dorset. Richard’s marriage to the heiress Lady Anne Clifford (1590–1676) in 1609 was an unsuccessful one. Anne’s diary provides a glimpse of her unhappy life at Knole and is a rare example of women’s writing from the 17th century.

Another historic document which offers a window into Richard and Anne’s Knole is the dining hall seating plan for over 100 servants. This plan reveals the various roles and hierarchies which kept the vast household running. Among the names recorded are Grace Robinson and John Morockoe who worked in the laundry and kitchen. Grace and John’s names are annotated ‘a Blackamoor’ which was a historic term often used to describe people of Black African heritage.

In 1624 Knole passed to Edward Sackville, 4th Earl of Dorset (1590–1652). Edward profited from his involvement in the Virginia Company and the Somers Island Company. They sought to establish profitable colonies along the eastern coast of North America and in Bermuda. Although they initially hoped to discover gold and silver, it was the lucrative tobacco trade—built on the exploitation of indentured and enslaved labour—that became their lasting source of profit.

The civil wars of the 1640s brought drastic change to Knole. Edward Sackville had pledged loyalty to the Crown and his wife Mary had been a royal governess. Their allegiances meant that Knole was raided and seized by Parliamentary soldiers. Following the execution of Charles I, Edward paid a fine of £2,415, to the new government and his estates were returned.

Frances Cranfield and Richard Sackville, 5th Earl of Dorset, were married in 1637. The union had been arranged by their fathers to restore both families’ social standing and the interiors of Knole, which had been stripped during the Civil Wars.

Frances’s legacy at Knole can be seen today in the rare survival of the English silver furniture by Gerrit Jenson which she commissioned in 1680.

Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset (1638–1706) did much to shape the collection at Knole. Charles was Lord Chamberlain and one of the ‘perquisites’, or ‘perks’, of this job was to take furniture no longer required in the royal palaces. This furniture included state chairs upholstered in rich textiles, a gold and silver bedroom suite and even a royal toilet, known as a ‘closed stool’. Most of the pieces are still on display today and are rare 17th century survivals.

Despite collecting material riches, Charles managed to virtually bankrupt Knole by gambling and spending recklessly.

John Frederick Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset (1745–1799), was twenty-four when he inherited his title. He had already embarked on a two-year Grand Tour of Europe at the age of twenty-three, travelling through France and Italy, spending £5,500 on paintings by European Old Masters such as Garofalo and Teniers, as well as classical sculptures. These purchases reflected his cultivated taste and his role in shaping the art collection at Knole.

John Frederick also commissioned new artworks by contemporary artists, including Gainsborough. Some of these works reveal details about life at Knole. He paid for a series of 46 servants’ portraits and a sculpture of his romantic partner, the ballerina Giovanna Zanerini (1753–1801), nicknamed La Baccelli. John Frederick was a friend and patron of Sir Joshua Reynolds and in 1775 he commissioned a portrait of the young Chinese scholar Huang Ya Dong (c.1753–c.1784) who had recently visited Knole.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Sackville family faced an inheritance crisis when only daughters were born: primogeniture - the custom of passing the estate to the eldest male - meant the ownership of Knole was passed to distant relatives

In 1908 Lionel Sackville-West inherited Knole and, along with wife Victoria, began to modernise the house. Under Victoria’s direction, a telephone was installed in the house, together with electricity, central heating, and hot running water in the bathrooms.

Vita Sackville-West (1892–1963), the only daughter of Victoria and Lionel, had a deep love for Knole which, as a woman, she was unable to inherit.

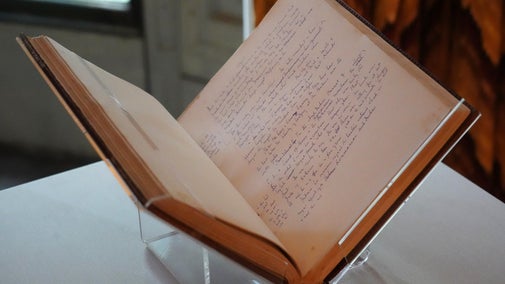

The house remained an important part of Vita’s artistic life, and her 1930 novel ‘The Edwardians’ is based on her childhood experiences. Vita and Knole inspired one of the most celebrated works of 20th-century literature, Virginia Woolf’s ‘Orlando’. Vita and Virginia were lovers, and the novel has been described as the longest love letter in literature. Woolf’s handwritten manuscript for ‘Orlando’ is in the National Trust’s collection at Knole.

Vita’s cousin Eddy Sackville-West (1901–1965) was the heir to Knole in the mid-20th century. He was a music journalist and novelist, writing much of his work in the Gatehouse Tower. Eddy was regularly visited by artists and literary figures of the Bloomsbury Group, including his friend and lover, the painter Duncan Grant.

Eddy never truly loved Knole, calling it ‘that big place in Kent’. In 1956 Eddy's father Charles, 4th Lord Sackville, passed ownership of the house to his nephew and Eddy's cousin, Lionel, who became 6th Lord Sackville.

In 1946 Knole was gifted to the National Trust to be opened to the public. The private apartments were leased back to the Sackville-West family, who also kept ownership of most of the parkland, the wild deer herd, and some of the contents of the house.

Knole has been a grand status symbol for over 400 years, but it has also been a place of work for servants, craftspeople and heritage professionals. In recent years, the stories of people who have lived and worked at Knole have been captured as part of the National Trust’s oral history collection. The earliest testimony remembers Rose Bondwick, who was a maid at Knole in the 1880s, and this can be found on the Knole Stories website. Among more recent interviewees are volunteers and staff who worked on the ‘Inspired by Knole’ project (2014-2019) which invested nearly £20 million in protecting, preserving and sharing the historic building and collection.

Sackville-West, Robert. 'Inheritance: The Story of Knole and the Sackvilles', 2010.

Cohen, Nathalie and Parton, Frances. 'Knole Revealed', 2019.

Strachey, Nino. 'Rooms of their Own: Eddy Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West', 2018.

Knole - five centuries of showing off, a short film by Dr Jonathan Foyle, 2013.

Knole Stories | Interviews about the history of Knole in Sevenoaks, Kent

Find out when Knole is open, how to get here, the things to see and do and more.

Explore Knole's showrooms to see one of the rarest and most well-preserved collections of Royal Stuart furniture, paintings, objects and textiles – on show since 1605.

Knole was built to impress. Come and explore the grandeur of its showrooms, the hidden secrets of the attics and the rooms Eddy Sackville-West called home in the Gatehouse Tower.

Virginia Woolf's 'Orlando' was inspired by Vita Sackville-West and Knole. A project to digitise the original manuscript means it is now accessible online.

Hidden above the grandeur of the showrooms lie Knole's attics - sometimes inhabited but more often used for storage, these spaces have evolved over the centuries with each generation. Find out more about the history of the spaces as well as witchmarks and unusual items that have been discovered.

A series of witchmarks, believed to ward off evil spirits, were discovered in a room built to accommodate James I at Knole following the Gunpowder Plot in 1605.

Knole has been home to and shaped by people who challenged conventional ideas of gender and sexuality. Discover their stories and the challenges they faced.

Discover Vita Sackville-West's connection to Knole; her colourful life and her literary legacy as a poet, novelist, gardener, biographer and journalist.

Learn about people from the past, discover remarkable works of art and brush up on your knowledge of architecture and gardens.