Discover more at Woolsthorpe Manor

Find out when Woolsthorpe Manor is open, how to book your visit, the things to see and do and more.

This small farmhouse near Colsterworth, Lincolnshire was the birthplace and home of Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727), widely considered the most important figure in the development of Western science. From a curious child to a remarkable young man, this manor was his sanctuary and his inspiration. His earliest experiments paved the way for his ‘Year of Wonders’, when the plague of 1665 saw Newton return to Woolsthorpe where he made some of his most profound discoveries.

Domesday Book records that Colsterworth was owned by two tenants-in-chief – the Archbishop of York and an un-named thane – in 1086, when it supported 21 households. Later, Woolsthorpe would become a separate manor, owned by several different families before Robert Newton (1563–1641), at least the fifth generation of his family to own and farm land in Colsterworth, purchased Woolsthorpe Manor in 1623. The majority of the present ‘T’-shaped house, built from Ancaster limestone, date from around this time. When Robert’s son, Isaac (1602–42) who had inherited the manor in 1641, died very shortly afterwards, his goods and livestock were valued at £459 12s 6d. The family into which Isaac Newton the scientist was born on Christmas Day 1642, just three months after his father’s death, was that of a substantial yeoman farmer.

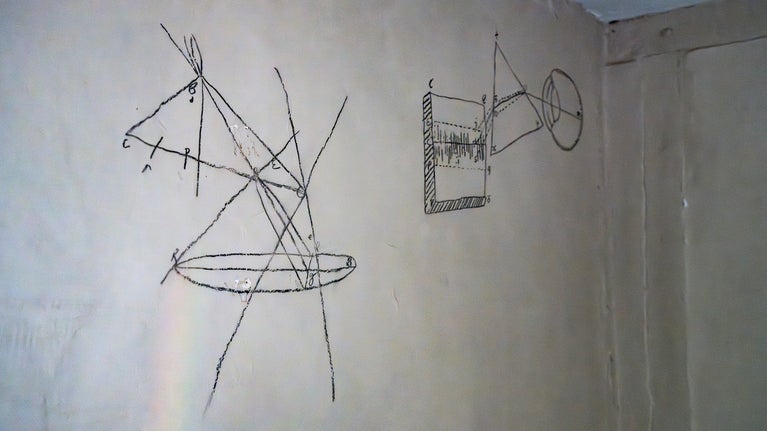

Growing up at Woolsthorpe, Isaac was inspired by the natural environment and landscape around him. He developed practical skills, making models and drawing. William Stukeley, Newton’s friend and biographer, wrote ‘The walls and ceilings were full of drawings, which he had made with charcoal. There were birds, beasts, men, ships, plants, mathematical figures, circles, & triangles.’ A stylised windmill, scratched into one of Woolsthorpe’s walls, survives today.

At 12 years old, Isaac was sent to The King’s School, a weekly boarding grammar school in nearby Grantham. He paid more attention to creating clever mechanical devices than to his textbooks and his skill in making and testing models flourished. He is said to have watched closely while a post-mill was constructed nearby and then made a small working model operated by a mouse. He lodged with Grantham’s apothecary, William Clarke, which gave him an early introduction to natural substances and chemicals. On 3 September 1658, during a great storm, 15-year-old Newton carried out his first experiment when he calculated the speed of wind.

When Newton was almost 17, his mother, Hannah (d. 1679), decided it was time for Isaac to come home and run the estate at Woolsthorpe. Isaac was totally unsuited to be a gentleman farmer and, after a disastrous nine months, it was decided that he should continue his education.

To Newton’s excitement, he was sent back to school. It was here that he acquired the mathematical skills and additional knowledge needed for entry into Cambridge University. The 18-year-old Newton left rural Lincolnshire for the first time to study at Trinty College, Cambridge in June 1661, just a year after the restoration of the Monarchy, which ushered in a new era of investment in science and discovery.

At University, Newton made two extended trips back to Woolsthorpe Manor between the summer of 1665 and spring of 1667. This was to escape the Great Plague that had started in London in 1665 and swept across the country. Like many town-dwellers, Newton retreated to the relative safety of the countryside.

In later life, Newton stressed that these periods at Woolsthorpe were the most intellectually fruitful of his entire life. That is why they are remembered as his 'Year of Wonders'.

For in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention and minded Mathematics and Philosophy more than at any time since.

In these intense periods at Woolsthorpe, Newton was freed from the restrictions of the limited curriculum and rigours of university life. He had the time and space to develop his theories on calculus, optics and the laws of motion and gravity.

A special apple tree stands in the orchard at Woolsthorpe. This is said to be the very tree from which an apple fell and prompted Newton, during his ‘Year of Wonders’, to ask why apples always fell straight down. The story of the falling apple that inspired Newton is a scientific legend but is believed to be broadly true. We know he was constantly inspired by the natural world around him which caused him to question, explore and experiment. Newton theorised that everything in existence is attracted to everything else and this attraction or power (or force) ties the universe together.

If working with optics and theorising about gravity was not enough during his ‘Year of Wonders’, Newton continued to tackle the mathematical problems that he had been contemplating at Cambridge. By the end of 1666, Newton had completed three papers on fluxions (early calculus), which culminated in his most intensive period of mathematic creativity.

After the Great Plague, Newton returned from Woolsthorpe to university at Cambridge and, six months later, was elected Minor Fellow of Trinity College. Two years after that, he was made Professor.

In 1684, Newton was approached by a young astronomer called Edmond Halley, while at Cambridge. Newton posed the theory that the curve to a mathematical formula was an ellipsis and Dr Halley asked for his calculations immediately. Halley went to great lengths to get Newton’s work into print. He coaxed him to produce the three books that became known as the Principia. Halley even paid for the publication himself as the Royal Society had run out of funds.

Newton first published the Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy – otherwise known as the Principia – in 1687. Originally written in Latin, it laid out his laws of motion, law of universal gravitation and an extension of Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. It was ground-breaking at the time and remains a cornerstone in the study of physics. It is generally recognised as Newton’s greatest scientific achievement.

In the early 1690s, England’s silver coinage had deteriorated both in quality and quantity. This crisis in the coinage was made worse by the simultaneous financial crisis caused by the unprecedented expenses of war with France and then Spain. In an age when professional economists did not exist, in 1695 the government sought advice from eight men known for their intellectual prowess or their experience in matters financial. The fact that Newton was one of this group testifies to the impact of the Principia.

He was instrumental in setting up the five country mints called for by parliament and Newton was then made Master of the Mint in 1699. He took office on 25 December, his birthday. The country boy had become a don at Cambridge and would now learn how to navigate London society and high politics. In 1701, he resigned his fellowship and chair in Cambridge. In 1703, the Royal Society elected Newton its president, a role he held until his death.

The War of the Spanish Succession of 1701 to 1714, a European conflict initiated by the desire to limit the power of Phillip V of Spain, required Britain to subsidise an alliance of European allies. This, of course, required the Royal Mint to issue coinage for the war overseen in part by Newton.

In order to finance the debts incurred during a decade of conflict, The South Sea Company was founded in 1711 to trade with South America, mainly in enslaved people. Newton invested in the South Sea Company multiple times, both before and after the South Sea Bubble burst in 1720. One of those times was at the peak of investors’ focus and he lost most of his fortune in the crash that followed. In early 1720 he liquidated the bulk of his South Sea Company holdings for a profit of £20,000. A few weeks later he appears to have gone back to the market and repurchased that same security at about double the price. He started investing as early as 1709 and by mid-1721 held £16,300 of stock worth £20,000.

It is not known how often Newton returned to Woolsthorpe from Cambridge and then London, but he continued to take an interest in the manor, visiting in 1679 and then, as some of his correspondence shows, in the 1680s. On his death in 1727, Woolsthorpe was inherited by John Newton (dates unknown), his uncle’s great-grandson. According to Stukeley, John Newton squandered his inheritance ‘by cocking [cock fighting], horse racing, drinking and folly.’ He was forced to sell the manor to Thomas Alcock, who in turn sold it in 1732 to Edmund Turnor of nearby Stoke Rochford. The property was then leased to a farming family named Woolerton, who were tenants for the next 200 years. Alterations were made to the house in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1942, the manor was purchased by Royal Society with the assistance of the Pilgrim Trust who then gave it to the National Trust for preservation.

The Trust has restored areas of the house and opened a Science Centre, where the next generation of scientists can begin to make their own discoveries.

Odlyzko, A. (2019) Newton's Misadventures in the South Sea Bubble. Notes and Records of the Royal Society, 73 29-59

Richard S. Westfall (2015) The Life Of Isaac Newton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 85-109

Woolsthorpe Global Histories Information Pack, Lynsey McLaughlin. 2024

Find out when Woolsthorpe Manor is open, how to book your visit, the things to see and do and more.

Woolsthorpe Manor is where Sir Isaac Newton was born and made huge scientific discoveries, and now visitors can carry out their own experiments in the science centre.

Find out more about the conservation work being done behind closed doors to care for Woolsthorpe Manor, including crucial conservation to protect the structure of the building.

From landscape gardeners to LGBTQ+ campaigners and suffragettes to famous writers, many people have had their impact on the places we care for. Discover their stories and the lasting legacies they’ve left behind.

Explore the objects and works of art we care for at Woolsthorpe Manor on the National Trust Collections website.