Ham House and Garden's collections

Explore the objects and works of art we care for at Ham House and Garden on the National Trust Collections website.

Ham House is home to a rare collection of cabinets, which are opened only twice a year to protect interiors from overexposure to light and avoid excessive wear on hinges and locks. Read on to discover more about the collection.

The collection of cabinets at Ham House includes examples of marquetry, lacquer and inlay, collected from countries including Japan, China, and the Netherlands as well as England.

Although cabinets and chests have been used since Roman times, in the 16th and 17th centuries they became valued as beautiful objects as well as objects of utility. They were status symbols that a wealthy family would aspire to own and display. As a result of this enthusiasm, the skill and technical expertise of cabinet makers reached new heights in the 17th century.

The collection of cabinets at Ham House includes examples of marquetry, lacquer and inlay, collected from countries including Japan, China, and the Netherlands as well as England.

Most (if not all) of the cabinets were collected by Elizabeth, Duchess of Lauderdale, whose signature authorised bills for payment to the craftspeople for their work. One example lists the many payments made to ‘Mr. Jensen Cabenett: Maker’.

Gerritt Jensen was one of the finest cabinet makers of the time. Most cabinets incorporated secret drawers and compartments, hidden to all but the owner, the maker, and trusted confidantes.

Cabinets were not only practical objects used for storage. They were also objects of art, often decorated in elaborate marquetry or other decoration. Cabinets were used to display and share items such as shells, jewels, or relics, that the owner would show to their friends to demonstrate their taste and education. Owners might also use secret compartments to hide confidential documents or letters.

These cabinets have always been objects to admire, opened only on occasion. By keeping the cabinets closed we keep the interiors protected from damage by light and pollution. The bright colours inside the cabinets show the difference that this careful management makes. Opening them only occasionally also protects the hinges from carrying too much weight, which would distort the structure of the cabinet over time.

Our Cabinets Unlocked events each spring and autumn are a chance to see inside the cabinets and explore their unique artisanship. The next Cabinets Unlocked will take place 16–31 May 2026. Follow the link below to discover more and plan a visit.

Elizabeth Murray, Duchess of Lauderdale, bought this cabinet after the English Civil Wars. Created around 1650-1660 in the Netherlands, this is the only known example of a cabinet completely veneered in ivory, both outside and inside. It contains at least two secret drawers and a secret compartment. The geometrical, rippled veneer creates a three-dimensional effect.

Ivory (elephant tusk) was a rare and valuable material in the mid-17th century, and was in demand in Holland for the decoration of fine cabinet work. Portuguese colonial expansion along the west coast of Africa in the early 17th century intensified the slaughter of elephants and the global trade in their tusks. This trade involved a network of merchants who facilitated the exchange between African suppliers and European buyers.

Oak and cedar, ivory veneer, 1650-1660. NT1139080

An Indo-Portuguese cabinet inlaid with intricate scrolling foliage of ivory. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Portuguese colonies and trading posts were established in India, in places like Goa. Portuguese colonial trade also fuelled the ivory trade along the West African coast.

Made around 1670, the front of the cabinet folds down to reveal a number of similarly decorated drawers. The brass escutcheon (the plate around the keyhole) and knobs that support the fall front are likely later additions.

Hardwood, ivory, brass, 1670-1699. NT1139628

Lacquered and inlaid with mother of pearl, these Japanese cabinets show images of blossom, buildings, and mythical birds. Likely made in Nagasaki in around 1670, they were collected by Elizabeth Murray, Duchess of Lauderdale, who gathered a large collection of Asian furniture in the 1670s. In the 17th century, Japan and China were admired for their civility and learning, and collecting such items was a powerful statement of taste and education.

These cabinets have stood in this room since the 17th century, when they were recorded in the 1677 inventory for Ham House. Their smaller size, compared to many of the other cabinets at Ham House, matches the Green Closet’s intimate and small dimensions.

Lacquered wood, mother of pearl, brass, c.1670. NT1139896 & NT1139897

Dating to around 1650, Ham’s intricate Japanese lacquer cabinet has stood in the Long Gallery since 1679. Lacquer comes from the refined sap of the Chinese lacquer tree, or Toxicodendron vernicifluum. Up to 200 layers are applied to achieve the lustrous black finish seen inside the cabinet. Each layer takes at least two days to dry, so the whole production would take several years.

The top of this cabinet was removed in the 18th century by renowned furniture maker George Nix, in order to create a table which now sits in the Queen's Closet.

Japanese lacquered wood, brass, carved and gilded softwood, c. 1650. NT1140084

Like many of the cabinets at Ham House, this 1675 walnut-veneered example has a secret compartment. Cabinet makers became skilled at creating intricate geometric patterns with thin cross-cut ovals of small diameter timber. This was known as oyster veneering, due to similarities in shape to oyster shells.

Walnut is a versatile and strong wood that was used by many fashionable furniture makers at this time. The ring handles for the long drawer at the base are formed in the shape of lion’s heads.

Walnut parquetry veneer, walnut, c. 1675. NT1139922

Influenced by French fashion, floral marquetry became highly popular in wealthy and royal circles in the late 17th century. This example at Ham is an early and exceptional example, made by the acclaimed Anglo-Dutch cabinet maker Gerritt Jensen. Elizabeth and John, Duchess and Duke of Lauderdale, were among the earliest patrons of Jensen. They helped to popularise floral marquetry, and Jensen’s work, in England between 1672-1683. This cabinet has stood at Ham since the 1670s.

If you look closely, you can see that every drawer and flower is subtly different. This demonstrates the quality of the piece since each design was made individually rather than cut from a consistent pattern. The three-dimensional effect is created by singeing the wood segments in hot sand.

Oak, pine, ebony, walnut, fruitwood, ivory and stained horn, brass, 1672-1683. NT1140106

Unlike smooth lacquered cabinets, this is an example of incised or ‘Coromandel’ lacquer. The design is created by cutting into a thick gesso-type base layer, then applying coloured lacquers. Coromandel lacquer is so named because it was shipped to Europe via the south-east Indian cost of Coromandel, by trading companies like the East India Company. It was often shipped in panels, and used to create furniture once it had arrived in Europe.

Here, an English maker has constructed the cabinet with a number of incised lacquer panels. If you look closely, you can see that it was not always considered important for the decorative scenes to line up or to be complete – or even sometimes to be the right way up.

Oak, pine, lacquered wood, japanned wood, carved and gilded softwood, c. 1675. NT1140111

Likely made in England around 1650, this miniature cabinet incorporates Chinese lacquer and japanned work. Smaller cabinets like these might have been used to store jewellery and other precious goods. The front doors depict two figures surrounded by flowers and foliage, and the inside is fitted with eight drawers decorated with flowering plants.

In 17th century Europe, China was admired for its civility and learning. The collection and display of Chinese and Japanese luxury goods was intended to display a person’s good taste and education.

Pine, beech, lacquered and japanned wood, brass, c.1650. NT1140094

This English commode was made in the French style, reflecting the design of similar examples which can be seen at the Palace of Versailles in France. It first appears in the Ham House inventories in 1844, described as ‘a very curious inlaid and gilt pier commode’.

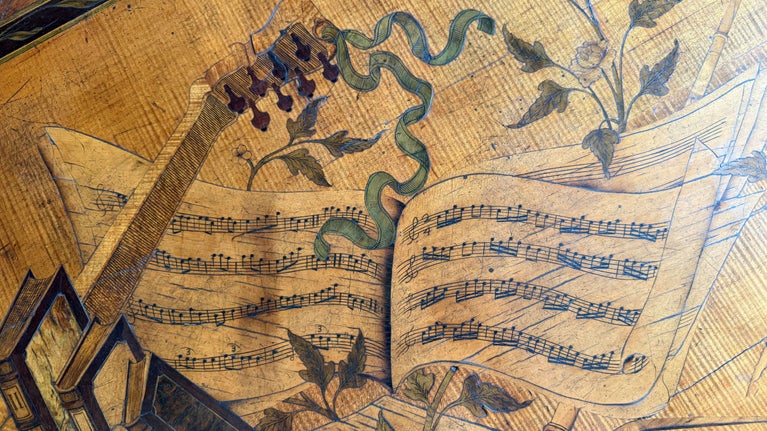

The marquetry top depicts a large trophy, open sheet music, musical instruments, books, writing implements, and a flowering branch. On each side, marquetry creates images of Grecian urns on pedestals.

Tulipwood, kingwood, purpleheart, sycamore, satinwood, ash, rosewood, gilt bronze. c.1722. NT1140073

This cabinet is unusual at Ham as it consists of a cabinet seated on top of a lower chest rather than a stand with legs.

Veneered in walnut parquetry and created around 1700, its bracket feet are probably later replacements for original ‘bun’ feet, like those on most other cabinets at Ham House. The cut of the parquetry creates an attractive design effect on the front of the drawers, which appear to look like the heads of birds.

Pine, oak, walnut and kingwood veneer, brass, c. 1700. NT1139997

Set within the shelves of the Library, the cabinet can be dated to 1672-4 when the Library was constructed. The scent of cedar repels insects that might damage books, so it is an ideal material to use in a library. This desk was made by joiner Henry Harlow, who also installed flooring and decorative woodwork at Ham House.

It was used by John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale and Elizabeth’s second husband. He was Secretary of State for Scotland and one of the first Lords of Trade and Plantations, under King Charles II.

Cedar, oak, pine, brass, 1673. NT1139047

This writing box, dating around 1680, contains everything the discerning 17th century gentleman needed to keep up with his correspondence. It contains several compartments for writing materials, including drawers and ink wells. It may have been used by John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale, Elizabeth’s second husband.

The writing box is made with kingwood, burr wood, and padouk parquetry. Padouk is a strong and durable reddish wood from West and Central Africa, including Nigeria, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Parquetry of kingwood, burr wood, padouk, c. 1680. NT1139630

The simple exterior of this 1675 olivewood and cocus wood cabinet conceals a striking interior. The dramatic coloured effect was created by incorporating the darker heartwood and the lighter sapwood into the veneered pattern, known as ‘oysterwork’.

Cocus was one of the most favoured materials for making oyster-veneered cabinets in the 1660s and 1670s. An expensive wood, it could be used economically to create this effect because of the thinness of the veneer.

Oak, walnut, olive and cocus wood veneer, c. 1675. NT1140035

This was recorded as a ‘box with an extraordinary Lock’ in the 1683 inventory. It is attributed to the cabinet maker Gerritt Jensen, and was made around 1675.

The complex lock has 36 hasps, all of which release on the turn of one key. At a time when banking was in its infancy and before safe-deposit boxes existed, boxes like these were essential for the storage of money and jewellery. Tucked behind the visible drawers are a set of secret drawers, perfect for concealing hidden valuables or private letters.

Oak, kingwood and olivewood parquetry, brass, c. 1675. NT1139747

Known to have been the personal writing desk of Elizabeth, Duchess of Lauderdale, the scriptor is covered in kingwood oysterwork veneer, made from thin slivers of wood cut obliquely across the branch to make the distinctive oval shape. The interior is veneered in rosewood.

Of extremely high quality and fine workmanship, this was almost certainly produced in London by a European maker – possibly the acclaimed cabinet maker Gerrit Jensen. The silver mounts in the shape of grotesque masks may have been supplied by London silversmith Josias Iback, who was paid £10 in 1673 for his work.

Oak, kingwood, silver, rosewood, brass and iron, c. 1672-75. NT1140278

This ornate cabinet first appears on the Ham House inventory of 1677 as the ‘Cabinet done wt Tortus Schell’. The interior is mirrored and with a chequerboard black and white floor, reminiscent of the marble floor in the Great Hall.

This cabinet is notable for its display of a variety of costly materials such as tortoiseshell, marble and ivory. Tortoiseshell was mainly sourced from the hawksbill sea turtle. This is now a critically endangered species and the trade in tortoiseshell was banned in 2014. The pale beige stone is Italian pietra paesina, or ‘landscape stone’. It is a rare type of limestone which forms naturally, but appears as though it is a landscape painted by a human hand.

Pine veneer, ebony and ebonised wood, tortoiseshell, ivory and satiné, marble, pietra paesina, gilt bronze, brass, c. 1650-1675. NT 1140050

Along with the ivory cabinet in the North Drawing Room, this ebony and kingwood cabinet is an early example of a fully fitted interior, rather than simple shelves. At first glance, it appears that there are 34 small drawers inside, but many of these are in fact double width drawers. They would have been ideal for storing documents.

Original inventories allow us to trace this piece of furniture through the centuries. Elizabeth, Duchess of Lauderdale, authorised a payment to a Dutch intermediary Mistress van de Huva for a ‘cabinet of black ebonie’, and the 1677 inventory for Ham House records a ‘black Abinie Cabinet’ in the Long Gallery.

Ebony, kingwood, gilt brass and bronze, oak. Netherlands, c. 1670. NT1139780

This is one of several ‘Indian boxes’ listed in the 1670s inventories for Ham House. ‘Indian’ mostly referred to Chinese and Japanese objects, some of which were shipped to Europe via the Coromandel coast in south-east India. This designation illustrates the vague understanding of Asian geography in the late 17th century. This coast was a hub for several European trading powers at this time, including the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC). This was the largest trading company in Asia, and generated huge profits through colonial monopolies.

Japanning on wood, brass, giltwood, c. 1675. NT1139778

Dating to around 1675, this incised lacquer and japanned cabinet was likely transported by the East India Company via trading ports on the Indian Coromandel coast. The lacquer elements would have been transported in panel form and then made up into a cabinet once it reached Europe. The japanned, imitation lacquer elements would have brought the piece together aesthetically. Cabinets of this size were ideal for storing small items like jewels and small curiosities like shells or corals.

Please note, the doors of this cabinet are kept closed to protect its fragile hinges.

Incised lacquer, japanned work, oak, brass, c. 1675. NT1139657

Made in around 1675, the heavy brass bandings on this strong box indicate that this piece was intended for security. Holes on the underside of the box allowed it to be attached to the floor of a carriage while travelling, for extra protection. The strongbox contains numerous hidden compartments, some no bigger than a match box, perfect for secretly storing jewels or letters. The outside is veneered in kingwood, and the inside veneered in rosewood.

Kingwood and rosewood veneers, walnut, brass, c.1675. NT 1139751

The inventory for Ham House records this ‘Scritore of Walnut tree done with Silver’ as stood in ‘His Graces Closett’ in 1677. This writing desk of exceptional quality was made for this room for John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale and Elizabeth’s second husband in around 1673.

It is veneered in burr elm and has traces of silvering on the legs, intended to match other silvered furniture and textiles in the room. The high quality and craftsmanship of this cabinet could point to the acclaimed cabinet maker Gerrit Jensen as its author. The Duke also had a matching reclining ‘sleeping chair’ in this room.

Walnut, burr elm and ebony veneer, silver, c. 1673. NT1139736

Explore the objects and works of art we care for at Ham House and Garden on the National Trust Collections website.

Explore the well-preserved interiors of one of the grandest Stuart houses in England, created to impress in the 17th-century by the Duchess of Lauderdale and her husband the Duke.

From the productive Kitchen Garden to the leafy Wilderness, there's plenty to enjoy on a stroll around Ham House's gardens in spring. Discover more seasonal highlights to explore on your next visit.

Set in historic buildings, the Orangery Café and shop offer inviting spaces to relax and treat yourself on your visit to Ham House and Garden. Discover our new seasonal menu of tempting treats and embrace the beauty of spring with our new collections in the shop.

Explore the rich history of Ham House on the banks of the River Thames near Richmond – a rare example of 17th-century life, treasures and architecture; hardly changed in 300 years.

Take a look behind the scenes and discover the work that goes into keeping this special place looking its best.

Thinking about volunteering at this special place? Here’s what you need to know.