Media

Our media centre provides the latest National Trust news, statements and supporting content for journalists.

Jump to

Contact us

Press contacts

If you are a journalist and would like information, interviews or spokespeople, use these contact details to speak to our national and regional media teams.

Press releases

Painting by Winston Churchill goes on UK public display for the first time, along with his painting coat, as Chartwell celebrates his passion for art

Amid the unrelenting pressures of leadership, Winston Churchill turned to painting as a powerful source of focus and calm – describing the practice as something that “came to my rescue.”

National Trust records huge increase in number of seal pups born at Orford Ness in Suffolk

As this year’s pupping season comes to an end, National Trust rangers at Orford Ness are celebrating the birth of 430 grey seal pups – an 88% increase on last year’s count and the surest sign yet that the colony is growing.

National Trust to release wild beavers in Somerset in landmark move for UK nature recovery

The National Trust has legally released into the wild a family and pair of Eurasian beavers at two sites as part of a wider release across the Holnicote Estate on Exmoor in Somerset, to contribute to one of the most ambitious and innovative river and wetland restoration efforts undertaken by the conservation charity.

“We can do bold things when people come together”: Giant response to appeal helps National Trust secure cherished Dorset landscape

Thanks to an overwhelmingly generous response to its fundraising appeal, the National Trust has been able to secure land surrounding the iconic Cerne Abbas Giant in Dorset, protecting this cherished landscape for nature, heritage and future generations.

New life from old barges: National Trust undertakes ultimate recycling mission to create island haven for endangered seabirds

A bold marine engineering feat is taking shape in the Blackwater Estuary, Essex, where the National Trust has sunk three decommissioned Thames lighters to form a brand-new island designed to help protect some of the UK’s most threatened seabirds.

Mount Stewart welcomes BBC Winterwatch to the historic estate

Mount Stewart is set to welcome the BBC Winterwatch team for their first ever broadcast from Northern Ireland.

National Trust welcomes philanthropist’s record-breaking donation as the charity unveils major plans for 2026

The National Trust has received the biggest cash donation in its 131-year history as philanthropist Humphrey Battcock has pledged £10 million in unrestricted funding. This comes as the Trust shares its upcoming plans to restore nature, end unequal access to nature and culture, and inspire millions more people to care for the world around them in 2026.

National Trust Director-General Hilary McGrady awarded CBE

Hilary McGrady, Director-General of the National Trust, has been awarded a CBE for services to heritage in The King's New Year Honours.

From drought to deluge: How 2025 tested the UK’s wildlife and landscapes

Britain has just endured a year of weather extremes that has pushed nature to its limits, putting wildlife and landscapes under severe pressure.

Mighty decorated giant redwood takes Guinness World Records title for the World’s Tallest Bedded Christmas Tree

A mighty decorated giant redwood at the National Trust’s Cragside in Northumberland has secured the Guinness World Records title for the World’s Tallest Bedded Christmas Tree.

Size does matter – National Trust launches appeal to help fund purchase and care of land around Cerne Abbas Giant

Conservation charity launches appeal to raise over £300,000 to help fund the purchase and care of land around the Cerne Abbas Giant

Mixed fortunes for Farne Islands’ seabirds in 2025 breeding season

Annual bird counts on the Farne Islands have revealed a mixed picture for the internationally important seabird colonies two years after several species were severely impacted by an outbreak of Avian Influenza.

First Sycamore Gap saplings (‘Trees of Hope’) to be planted this National Tree Week

The first of the 49 Sycamore Gap tree saplings given by the National Trust to individuals, community groups, and organisations across the UK will be planted this weekend.

Nature isn't the enemy - it's time for The Chancellor to change the record

Ahead of the Budget, Director-General Hilary McGrady writes in The Times that the Treasury must recognise the value of nature.

National Trust invites nature lovers to tune in for live "pup-dates" from England’s largest grey seal colony

Blakeney Point on the Norfolk Coast is once again the stage for one of England’s most extraordinary wildlife spectacles, the annual grey seal pupping season.

Record number of National Trust members stand for election to charity’s Council at Annual General Meeting

National Trust members have today taken part in the Trust’s 130th Annual General Meeting (AGM), which was held today in STEAM Museum, Swindon, and online.

National Trust and Admiral announce three-year partnership focusing on natural flood prevention in England and Wales

The National Trust and Admiral have joined forces in a new strategic partnership that brings together nature conservation and community protection.

Rare spider rediscovered in Britain after 40 years – just in time for Hallowe’en

A critically endangered wolf spider, unseen in Britain for four decades, has been rediscovered on the Isle of Wight, marking a major conservation success.

National Trust to take on ‘birthplace of the industrial revolution’ site at Ironbridge Gorge from spring 2026

From spring 2026 the National Trust will take on the care and management of the museums, buildings and monuments that represent the birthplace of the industrial revolution within the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site in Shropshire.

National Trust launches ‘Wild Senses’ campaign to reignite nature connection this autumn

As the days grow shorter and colder, the National Trust is calling on the public to resist the seasonal retreat indoors and instead embrace the sensory richness of autumn through its new nationwide campaign, ‘Wild Senses’.

Ancient artefacts emerge from recently excavated Roman settlement on the Attingham Estate

Following the announcement of a landmark geophysical survey by the National Trust last year – which identified significant archaeological features including Roman villas, cemeteries, roads, and Iron Age farmsteads – recent excavations at one of the sites have uncovered remarkable insights into life on the fringes of Wroxeter Roman City.

Wicken Fen becomes first UK nature reserve to record 10,000 species

Wicken Fen nature reserve in Cambridgeshire has recorded its 10,000th species of wildlife – becoming, experts believe, the first known UK site of its kind to do so

Berry good autumn expected despite the record-breaking hot summer and drought

National Trust experts are tipping a long, colourful autumn display at many of the charity’s gardens, parklands and woodlands this year, thanks to plentiful sunshine and welcome late rain which put the brakes on a ‘false autumn’ caused by hot, dry conditions.

Creating a sustainable future for the National Trust update

In July we announced the need to make savings due to sustained cost pressures that are affecting many charities, and to put us in the best position to deliver our new 10-year strategy.

Sky Gardening Challenge winners announced at celebration event

The National Trust has announced the winners of the 2025 Sky Gardening Challenge, which encouraged Greater Manchester residents to green the city’s skyline by planting up their balconies and window boxes.

Victorian rockstar’s globetrotting piano that survived shipwreck and scandal comes home to Northumberland after 150 years

A grand piano with a history as dramatic as any Victorian novel has returned to its rightful home at the National Trust’s Cragside in Northumberland.

National Trust announces creative commission on second anniversary of Sycamore Gap tree felling

Two years on from the illegal felling of the Sycamore Gap tree, the National Trust is today announcing a major creative commission, inviting artists, organisations and creative agencies to breathe new life into the wood saved from the felled tree.

Bumper crops of apples and pumpkins at National Trust gardens despite drought and record-breaking hot summer

The National Trust has confirmed a bumper harvest at many of its gardens, with fruit and vegetable crops also ripening and ready for harvest weeks earlier than usual.

Slow looking, deep feeling: the National Trust invites mindful viewing through Rembrandt ‘selfie’

The National Trust is inviting visitors to slow down and reconnect - with themselves and with art - through a year-long nationwide tour of one of its most celebrated paintings: Self-portrait wearing a Feathered Bonnet by Rembrandt van Rijn.

Back to the future: Cliveden’s reimagined Long Garden looks ahead while cherishing its past

The National Trust has completed a major restoration of the Long Garden at Cliveden in Buckinghamshire, breathing new life into one of the estate’s most iconic formal spaces.

Surge in 18–25-year-old new members as National Trust annual report reveals growth of 39%

The number of new 18–25-year-olds choosing to join the National Trust grew 39% in the last year, the charity’s annual report, released today, has revealed.

Water voles return to the River Wey after 20 year absence

Britain's fastest declining mammal, the water vole, is being returned to the River Wey catchment in Surrey, Sussex and Hampshire, having previously been declared locally extinct.

Butterfly numbers at historic forest hit 17 year high

National Trust rangers at Hatfield Forest in Essex are celebrating a bumper year for butterflies as the number of species recorded reaches a 17-year high.

Hot and dry weather reveals hidden features under the lawns of historic landscapes

Lost buildings under lawns and parkland across the country are being revealed this summer, as a result of the exceptionally dry weather this year.

Families help unearth everyday treasures at home of Isaac Newton’s mother, close to the famous apple tree that inspired the scientist’s work on gravity

Archaeologists from the National Trust have revealed a selection of everyday objects from the site of a house built for Isaac Newton’s mother, in a field next to the famous apple tree which inspired some of his great scientific advances.

Masterpiece bookcases by Robert Adam come home to Croome Court permanently from the V&A

A monumental set of 18th-century bookcases, designed by renowned architect Robert Adam for Croome Court in Worcestershire will go on display in the house once more thanks to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London.

Seeds sown to bring nature closer to 10 million people across the UK in the next 10 years

A new mission to bring nature to towns and cities across the UK will benefit millions of people living in urban neighbourhoods in the UK over the next decade.

Castlefield Viaduct ‘sky park’ receives £2.75m funding towards major extension

The National Trust has today announced an exciting development in the transformation of a Grade II Victorian viaduct in the heart of Manchester.

National Trust explores climate adaptation in new 'Garden for the Future’ at Sheffield Park and Garden, in landscape’s first major refresh in more than 70 years

A new Garden for the Future has been opened at Sheffield Park and Garden in East Sussex, the first major planting refresh of the Grade-I listed landscape since it came into the care of the National Trust in 1954.

Discovery of rare medieval music brings sounds of monks back to Devon abbey for first time in 500 years

For the first time in nearly five centuries, Buckland Abbey in Devon will resonate once more with the sacred sounds of monastic music, thanks to research into a rare 15th-century manuscript and a collaboration between the National Trust and the University of Exeter supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council.

Downturn in fortunes: Long Nanny terns face mounting pressures from climate change and disease

A significant breeding site for some of the UK’s rarest seabirds including the Arctic tern, has seen the number of pairs returning to breed drop by nearly a third (30 per cent) this summer.

Unique red riding breeches take centre stage as menswear exhibition explores Savile Row flair of 1930s aristocrat

This summer, a new exhibition at Anglesey Abbey in Cambridgeshire delves into the world of mid-20th century men’s fashion and bespoke tailoring.

The love that defied convention seen in dazzling Victorian sculpture on display after years feared lost

The National Trust’s Dunham Massey in Cheshire has acquired a long-lost masterpiece of Victorian silverwork – Stags in Bradgate Park – which was commissioned by a former owner in a defiant gesture to the society that shunned him.

Completion of Wicken Fen peatland restoration project provides hope for the future and sheds light on the past

The completion of an ambitious peatland restoration project at Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire offers a promising future for this vital landscape and the wildlife it supports. This work has also uncovered important information about the area's history.

National Trust nears 900 miles of protected coastline on 60th anniversary of fundraising campaign

Almost 900 miles of coastline in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are now protected for the nation thanks to the generosity of the UK public, the National Trust has announced.

Exmoor estate sees resurgence of rare butterfly once on the brink of extinction

One of the UK’s rarest butterflies, the heath fritillary, is seeing a significant rise in numbers and range on the National Trust’s Holnicote Estate on Exmoor - bucking the national trend of butterfly decline.

Largest collection of Turner's works outside London brought together to explore the inspiration the artist drew from a remarkable landscape

The relationship between Britain’s most renowned artist and the landscape which inspired him is being explored in a new exhibition by the National Trust.

The clue is in the poo! Secrets to boosting the recovery of at risk pied flycatcher could be revealed in new research into bird droppings and choice of nest location

Academics from Liverpool John Moores University, along with rangers and volunteers from the National Trust, are working together to explore what factors make pied flycatchers, a fly eating bird slightly smaller than a house sparrow and on the amber list of conservation concern, decide where to nest on the Longshaw Estate in the Peak District. The study will also provide data to uncover how these birds are adapting in an ever-changing world.

National Trust calls for investment in historic environment as research uncovers ‘deep emotional connection’ between Brits and their local heritage

Heritage should play a central part of the Government’s plans to promote national renewal, following new research that shows how highly the British public value their local history.

Visitors urged to stop leaving coins which damage the famous Giant’s Causeway stones

A giant issue with coins has emerged at the Giant’s Causeway, where a ritual by tourists to wedge coins into the cracks in the basalt rock columns of the Causeway is causing damage to the World Heritage Site.

BBC Springwatch returns with three weeks of live programmes from two new locations as it marks its 20th anniversary

On its 20th anniversary year Springwatch returns to BBC Two and iPlayer from Monday 26 May with presenters Chris Packham and Michaela Strachan leading three weeks of wildlife wonder from a new location - the National Trust’s Longshaw Estate in the heart of the Peak District.

Puffin count underway as National Trust marks centenary year of caring for the Farne Islands

This year’s puffin count is underway on the Farne Islands, an internationally important sanctuary for the 200,000 seabirds that return each summer to breed, in what is also the National Trust’s 100th year of caring for the archipelago in the North Sea.

Statement on the outcome of the Sycamore Gap trial

Our response to the outcome of the trial concerning the Sycamore Gap tree at Hadrian's Wall, Northumberland, which was illegally felled in September 2023.

New exhibition explores how fashion in art expressed power and personality - and is inspiring a new generation

Take a captivating journey through the glamour and extravagance of fashion in art at the National Trust’s Polesden Lacey in Surrey, the former home of Edwardian society hostess, Margaret Greville.

Birds, beetles and butterflies: conservationists reveal wildlife affected by UK fires

The National Trust has laid bare some of the varied species of wildlife that have been affected by this month’s spate of wildfires.

National Trust river project at Holnicote in Somerset, wins prestigious UK River Prize 2025

An ambitious project aimed at restoring natural processes and ecological function in Somerset’s River Aller and Horner Water catchments has triumphed at the prestigious 2025 UK River Prize awarded by the River Restoration Centre (RRC), winning the Catchment Restoration Award.

Puffins spotted on the Farne Islands as visitors are welcomed for spring

The first puffins return to the Farne Islands as the National Trust welcomes visitors back onto Inner Farne this spring. 2025 marks 100 years of the islands being in the care of the National Trust.

£5m of funding from Garfield Weston Foundation will help ‘turn the tide’ for nature on a huge scale says the National Trust

The battle against both the nature and climate crises is being stepped up on land cared for by the National Trust at four locations in England, thanks to £5m of funding support from the Garfield Weston Foundation to tackle nature conservation at a landscape scale.

Environmentalists and farmers unite to urge Government to avoid hammer blow to nature and food security

Over 50 environment and farming groups are urging the Government not to cut the already inadequate nature-friendly farming budget for the Department for the Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (Defra) any further.

New nursery acquisition at world-famous Bodnant Garden will help secure living collection for next 150 years

A vital new nursery space at the National Trust’s Bodnant Garden in Conwy, North Wales, will help safeguard the world-famous garden’s living collection for generations to come.

Showy season of sensational blooms expected for this year’s blossom display as charity encourages workers to take a Big Blooming Break

The spring equinox (Thursday 20 March) sees the start of the National Trust’s annual Blossom campaign aimed at encouraging Brits to get outdoors to enjoy this fleeting moment of spring.

Most highly decorative Tudor gallery in Europe safeguarded by conservators

The most highly decorative Tudor gallery in Europe, visited by King Henry VIII and two of his ill-fated wives, has had its future secured following a six-month conservation programme by the National Trust.

Saving a species: ‘Living library’ of Britain’s rarest native tree takes root at Killerton

The National Trust is creating a ‘living library’ of trees in east Devon in efforts to help save Britain’s rarest and most threatened native species, the black poplar.

‘Like a complex puzzle’: Country's oldest stumpery – the inspiration for a royal garden feature – reinstated after major renovation project

The Stumpery at Biddulph Grange Garden in Staffordshire – a masterpiece of Victorian garden design – may now be the largest in the country, as well as the oldest, following renovation and expansion by the National Trust.

In the pink – sunshine and steadier temperatures help National Trust gardens bloom

Magnificent magnolia displays have come out in full force at many National Trust gardens across the south-west following a week of continuous sunshine and milder temperatures, dipping nature in hues of pink just weeks ahead of the start of the National Trust’s annual blossom campaign on the 20 March.

Going wild! Historic first official wild beaver release marks new era for nature’s recovery in England

In a landmark event for nature conservation, the National Trust has legally released (today – Wednesday 5 March) the first two pairs of Eurasian beavers to live in the wild in Purbeck, Dorset. This historic moment follows a ground breaking policy announcement by Defra and Natural England last Friday (28 February), paving the way for wild beaver releases.

Spring’s on the way! 1 millionth snowdrop planted by visitors at the National Trust’s Wallington estate, completing 10-year project

Every February half-term for the last nine years, visitors and families have helped to plant hundreds of thousands of snowdrops at the National Trust’s Wallington in Northumberland. On Sunday 2 March, visitors put on their gardening gloves one more time to help plant the final 100,000 snowdrops – bringing the total snowdrops planted to 1 million.

Restored portrait of Churchill’s ancestor and hero – gifted to lift his wartime spirits – on public display for the first time

The National Trust’s Chartwell, cherished Kent home of Sir Winston Churchill, this weekend unveils a newly restored portrait of Churchill’s ancestor and hero, the 1st Duke of Marlborough. It is the first time in its history that the painting has been on public display.

Small wooden box belonging to Rudyard Kipling identified as rare casket in Barniz de Pasto technique made by South American craftsmen

A small wooden box which may have been a holiday souvenir either brought back by Rudyard Kipling, or given to him as a gift by his daughter, has turned out to be a very rare handmade South American casket.

Beatrix Potter’s doll’s house back on display after conservation work to items featured in beloved author’s “The Tale of Two Bad Mice”

A doll’s house and its contents, once owned by children’s author Beatrix Potter, has gone back on display in the Lake District after being given conservation treatment by National Trust experts. The collection of tiny pieces of furniture, plaster food, cutlery and other items inspired many illustrations in her book ‘The Tale of Two Bad Mice’.

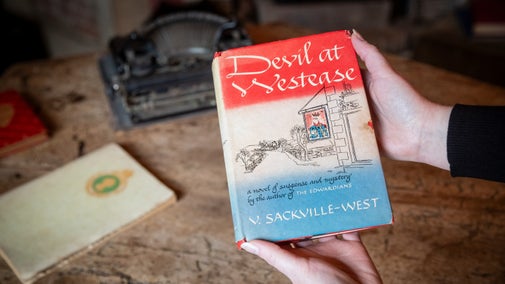

Get ‘between the covers’ with Vita Sackville-West as exhibition explores her life and literature for the first time

Vita Sackville-West is known the world over as one of the 20th century’s most influential gardeners and whose same sex relationships with writers like Virginia Woolf have been well documented. However, Vita’s output as a writer who explored love and identity was prolific, but much of her work has fallen into obscurity. For the first time at Sissinghurst, in Kent, the home Vita shared with her husband Harold Nicolson, a new exhibition by the National Trust will put the spotlight on her writing through ten of her works.

New wood pasture to help amplify nature’s chorus in Purbeck

A project is underway to amplify nature’s chorus across Purbeck in Dorset by restoring areas of wood pasture, a prime habitat for Britain’s much-loved, native songbirds.

More than 10,000 trees toppled and extensive damage to gardens and estates following hurricane force gales, says the National Trust

Storm Éowyn has caused extensive damage to gardens and estates cared for by the National Trust across Northern Ireland and the north of England, with more than 10,000 trees toppled.

National Trust to plant woodlands and woody habitats equivalent in size to over 800 football pitches with support from England’s Community Forests this winter

This winter, the National Trust and England’s Community Forests are working in partnership to create around 519 hectares (1,282 acres) of new woodlands and woody habitats across England, equivalent in size to more than 800 football pitches.

National Trust launches HistoryScapes storytelling app to offer ‘time travel experience’ through voices from the past

Three National Trust properties, in partnership with the University of Exeter, feature in an immersive new app, HistoryScapes, that brings their estates’ histories to life through the eyes of ordinary people: a carpenter, a mill worker and a broom maker.

National Trust to host newest giant sculpture by Luke Jerram: Helios

Throughout 2025 the National Trust has announced it will display Luke Jerram’s newest sculpture, Helios, at locations in England, Wales and Northen Ireland. The Trust aims to make this dazzling new artwork as accessible to as many people as possible over the next year.

Director General marks National Trust’s 130th birthday by unveiling ambitious plans for the next decade

The National Trust is marking its 130th birthday by unveiling hugely ambitious plans for the next decade and beyond, as it launches a new 10-year strategy.

Lurch from drought to deluge sees another mixed year for UK wildlife as National Trust thanks supporters who’ve helped hundreds of projects

With 2024 declared the world’s hottest year on record earlier this month, ferocious storms bookended a very wet and mild year in the UK, prompting fresh fears for climate change’s impacts on wildlife.

Super seed smoothie helps struggling Chiltern juniper bushes back to strength

National Trust rangers in the Chiltern Hills in Buckinghamshire are lending a helping hand in the reintroduction of their local juniper trees by blending a super seed smoothie to halt the species' decline and encourage its long-term reestablishment across five sites.

‘Exceptional’ Head Gardener John Lanyon hangs up his trowel after 27 years at National Trust gardens

Respected, award-winning horticulturist John Lanyon is set to retire after 27 years as Head Gardener with the National Trust, and 42 years in professional horticulture.

Tower built for a King at Corfe Castle to be opened to the public for the first time since the English Civil War

For the first time since 1646 when Corfe Castle was destroyed in the English Civil War, the public will be able to access a tower that was built for King Henry I five-hundred years earlier.

Sycamore Gap saplings to spread hope throughout the nation as recipients of the 49 ‘Trees of Hope’ announced

The National Trust has announced the recipients of the 49 ‘Trees of Hope’ Sycamore Gap saplings being gifted to individuals, groups, and organisations across the UK. The big reveal in National Tree Week follows the charity’s invitation on the anniversary of the felling of the much-loved tree at the end of September for applications for one of the saplings grown from its seed.

Presenter and architect George Clarke switches on the lights of the UK’s Tallest Living Christmas Tree at Cragside

TV presenter and architect George Clarke switched on the lights of the UK’s Tallest Living Christmas Tree at Cragside on Wednesday 27 November, officially kickstarting the property’s countdown to Christmas.

First grey seal pup of 2024 is born at Orford Ness

The first grey seal pup of this winter has been born at Orford Ness in Suffolk, marking the fourth consecutive year of successful breeding at the coastal site.

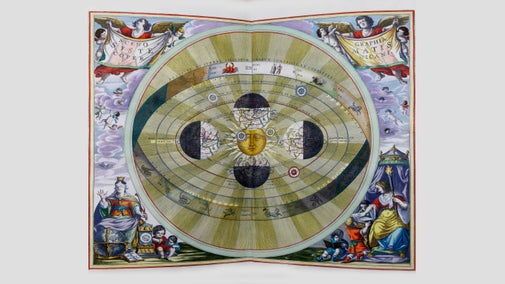

‘Spectacular’ rare 17th-century ‘star atlas’ from Golden Age of Dutch map-making goes on display for first time

One of the world’s finest and rarest 17th century atlases is set to go on display for the first time at the National Trust’s Blickling Estate in Norfolk, following specialist conservation.

Centuries of colour history to be revealed as National Trust establishes new laboratory to research paints used in the past

New insights into the colourful world of the past will be revealed at a new National Trust archive of thousands of historic paint samples. The new facility based in Kent has been made possible thanks to funding of £621,962 from the UKRI Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

‘Crumbling cloisters’ at Whipsnade Tree Cathedral World War I memorial restored for people and nature

Whipsnade Tree Cathedral in Bedfordshire, one of only three tree cathedrals in the UK, is undergoing vital conservation works to restore its natural, architectural beauty for people and nature after being devasted by ash dieback over the past five years.

New £10m centre to tackle the health impacts of climate change

A new Centre focused on delivering research on climate change and its impacts on health that will address climate-environment-health inequalities across each life stage is being created by the University of Exeter, in partnership with the National Trust.

National Trust members vote in support of offering a 50% plant-based menu across Trust cafés

National Trust members have today taken part in the Trust’s 129th Annual General Meeting (AGM), which was held today in Newcastle Civic Centre and online.

Orford Ness ‘crawling’ with spiders as survey reveals new record of rare spider species for the wild and remote location

As we approach Halloween, recent surveys by spider experts have revealed that the wild and remote Orford Ness, cared for by the National Trust, is ‘crawling’ with spiders. A total of 55 species of spider have been identified, including 12 believed to be nationally rare or scarce, and a first-time record for the Suffolk coast of the nationally rare Neon pictus, a tiny jumping spider.

Pioneering river restoration declared a success delivering incredible benefits for nature and people within 12 months of completion

A year on from the completion of a three-year project on the National Trust’s Holnicote Estate in Somerset to reconnect a section of a river to its floodplain – the innovative ‘Stage 0’ river restoration technique, first pioneered in Oregon, USA – has been heralded a success.

New plaque honours Birmingham poet and activist Benjamin Zephaniah

A blue plaque commemorating Birmingham poet and activist Benjamin Zephaniah has been unveiled in his home city.

Cold, wet year and thriving slugs bring disappointment to the pumpkin patch as Halloween approaches

Cold, wet weather and a boom in slug populations have led to disappointing pumpkin harvests at a number of National Trust gardens, as many gear up for autumn and Halloween celebrations.

National Trust predicts autumn likely to be ‘a mixed bag’ thanks to a ‘soggy’ year as most trees hold on tight to their leaves

With October underway, National Trust rangers and gardeners are preparing for a "mixed bag" of autumnal displays across gardens, parklands and woodlands in England, Wales and Northern Ireland due to the cool and wet conditions preceding the yearly spectacle.

National Trust appoints Sheila Das as Head of Gardens and Parks

The National Trust has appointed Sheila Das as the charity’s Head of Gardens and Parks.

Sycamore Gap Tree One Year On - 'Trees of Hope' case studies

The National Trust has this morning (Friday 27 September) announced more details to help inspire people and communities to apply for one of the 49 ‘Trees of Hope’ – grown from seed from the sycamore gap tree which formerly stood proudly in the gap, towering above Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland National Park, until it was illegally felled, one year ago.

Filling the Gap - Sycamore Gap Tree lives on as hope prevails with iconic tree’s legacy

A year after the illegal felling of the iconic Sycamore Gap tree which formerly stood proudly in the gap, towering above Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland National Park, the National Trust and Northumberland National Park Authority are today (Friday 27 September) revealing more details about the legacy of the tree – and its plans for how hope will prevail in the face of tragedy.

Clean air and fire breaks help silver-studded blue butterflies go for gold as butterfly count at Dorset nature reserve sets new record

Butterfly experts have recorded the highest-ever numbers for silver-studded blue butterflies on the Studland heaths in Dorset, cared for by the National Trust, bucking the trend of an otherwise challenging year for butterflies.

Puffin population declared ‘stable’ on the Farne Islands as results of first full count for five years are confirmed

Puffin numbers on the remote Farne Islands, off the coast of Northumberland, have seen a 15 per cent increase with the population declared as ‘stable’, after the first full count of the precious seabirds since 2019.

It’s a bird! It’s a crane!: Chick of Britain’s tallest bird fledges at Wicken Fen for the first time

A pair of cranes at the Wicken Fen National Nature Reserve in Cambridgeshire, cared for by the National Trust, has successfully fledged a chick for the first time since choosing to breed at the site in 2019.

New flower garden to bring surprise, theatre and delight to almost complete Georgian estate, the final work of ‘Capability’ Brown

After 10 years of planning, groundworks have begun to create a new flower garden at Berrington Hall in Herefordshire – home of ‘Capability’ Brown’s final landscape design – and to recapture the surprise and delight of the Georgian Pleasure Ground.

National Trust announces plans for £1 million in garden investment, as its collaboration with Blue Diamond Garden Centres enters third year

The National Trust has announced that £1 million of funding from Blue Diamond Garden Centres will be spent on garden and plant conservation projects, as it enters the third year of its brand licensing agreement with the garden centre group.

Conservation of rare State Bed cover reveals a patchwork of hidden details and wartime 'make do and mend'

A rare cover from a 300-year-old bed has gone on public display at the National Trust’s Erddig Hall and Garden in Wrexham following conservation and research which has revealed previously unknown details about its history, make-up and the early 20th -century wartime needlework that saved it from ruin.

12% day tripper boost to National Trust sites reveals new visitor trend

People are still prepared to spend money on a great day out despite the continued impact of the cost of living crisis, with the National Trust’s Annual Report revealing a 5% increase in visitor numbers to their pay for entry places in 2023/24 compared with the previous year.

National Trust brings nature back to an area twice the size of Manchester in less than a decade

The National Trust has achieved its aim of creating or restoring 25,000 hectares (61,776 acres) of priority habitat (habitats of principal importance for wildlife and supporting ecosystems) on its land by 2025, a target set in line with the charity’s conservation goals announced in 2015.

Striking jewel by ‘creator of genius’ to royalty and film stars returns to historic house where it was made

A gold and diamond ring made by Louis Osman, a leading figure in 20th-century design, has gone on public display at the Northamptonshire home where he lived, worked and drew inspiration for more than a decade. Osman is best known for designing and making the coronet worn by the then Prince of Wales at his investiture in 1969.

Watch the birdie: Project to transform golf course into wetlands to benefit migratory birds gets underway

Work starts at Sandilands near Sutton-on-Sea next week to transform a former golf course on the Lincolnshire coastline into a 25-hectare (62 acre) wetland nature reserve.

National Trust visitors’ summer spending paints a picture of rainy holidays fuelled by sandwiches, cakes and ice cream

As millions prepare to enjoy the last long weekend of summer, the National Trust looks back at what has been a bumper season for ice creams, scones, cakes, curry, adventures and umbrellas.

National Trust urges people to ‘leave no trace’ this bank holiday weekend to help protect nature and the country’s favourite outdoor spots

Ahead of the typically busy August bank holiday weekend the National Trust is urging people to ‘leave no trace’ after a prominent increase in illegal fly camping and littering over the summer months at countryside and coastal locations.

Dunwich heather back in bloom after remarkable recovery

Dunwich Heath, a rare heathland habitat cared for by the National Trust on the Suffolk coast is showing signs of recovery, with its patchwork of pink and purple heather back in bloom after being severely impacted by extreme heat and drought in 2022.

Lady Macbeth costumes worn by idol of Victorian theatre Ellen Terry go on display at her former home

The fashion worn by stars at the Met Gala or the Oscars may be hotly anticipated, but 130 years ago it was ‘pop idol’ Ellen Terry who drew the crowds when she stepped out on stage in costumes that drew gasps from the audience.

National Trust Saltram first outdoor cultural site in the UK to trial pioneering NaviLens technology to aid partially sighted people

This week National Trust Saltram in Plymouth has become the first outdoor cultural site in the UK to trial the use of a pioneering navigational app for partially sighted visitors.

Andy Sturgeon-designed Mediterranean Garden boosts climate resilience and biodiversity as Beningbrough Hall continues its revival

A new Mediterranean Garden, designed for a changing climate by award-winning garden designer Andy Sturgeon, has been unveiled at the National Trust’s Beningbrough Hall near York.

Sprouting Sycamore! Delight as Sycamore Gap tree shows signs of regrowth

Encouraging signs of new life are peeking through at the site of the illegally felled Sycamore Gap tree in Northumberland. Growing from the base of the stump, eight new shoots have emerged giving hope that the tree lives on, ten months since it was felled in 2023.

Mind bog-gling new study reveals Marsden Moor stores over a million tonnes of carbon

To mark World Bog Day (Sunday 28 July), peatland experts working together with the National Trust at Marsden Moor in West Yorkshire have found that the moor’s peat stores at least one million tonnes of carbon, further evidence that peatlands can play a crucial role in tackling climate change.

Life of an 18th century ‘lady of the house’ and her struggles to fit in are explored for the first time at National Trust’s Nostell

The moving story of an 18th century woman struggling to fit into her role and responsibilities in a grand country house is being explored at the National Trust’s Nostell in West Yorkshire.

New report reveals that nature-friendly farming budget is inadequate to meet climate and nature targets

New economic analysis, published today [23 July 2024], demonstrates that the current agricultural budget is significantly less than what is required for the UK farm and land management sector to help tackle the nature and climate crisis.

Rare survivals of decorative paper cutting by schoolgirls in the 17th century found under floorboards at Sutton House

Rare surviving examples of decorative paper cutting by schoolgirls in the 17th century have been identified at the National Trust’s Sutton House in London.

Heart stopping beauty of Sycamore Gap brought to life by ‘Heartwood’: An exhibition of five tree prints created from a disc of the felled tree’s trunk

A collection of five bespoke tree prints entitled ‘Heartwood’, created from a disc of the trunk of the felled iconic Sycamore Gap tree, will go on public display today [Monday 15 July]. The National Trust approached printmaker Shona Branigan, known for her detailed and evocative tree prints, to create the commemorative artworks that will be exhibited at four locations along the span of Hadrian’s Wall.

Beaver release at Wallington going 'swimmingly' as baby kit is born one year on

The National Trust has announced the birth of the first baby beaver (a kit) to be born on the Wallington Estate in Northumberland for over 400 years, following the release of a family of Eurasian beavers last year.

Archaeologists restore shrinking Bronze Age White Horse, Britain’s oldest chalk figure

Archaeologists from the National Trust and Oxford Archaeology have completed work to restore the profile of Britain’s oldest chalk figure, the Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire.

Patchwork of wildflower meadows wow for National Meadows Day as rare grasslands on North Devon coast peak in first full bloom to benefit nature and people

On the north Devon coast 90 hectares (222 acres) of newly created rare wildflower meadows have reached their first full bloom, to create a vibrant burst of colour to the summer countryside in time for National Meadows Day (Saturday 6 July).

National Trust's asks for the new government

Our priority asks for the new government after the General Election held on Thursday, 4th July 2024.

Rangers hopeful of about ‘tern’ in fortunes for graceful seabirds at Long Nanny after colony devastated by bird flu last year

National Trust rangers who keep close watch over Britain’s largest mainland colony of Arctic Terns at Long Nanny on the coast of Northumberland are holding their breath at a critical time in the breeding season to see whether the colony has managed to escape avian influenza, bird flu, this year.

Largest geophysical survey ever undertaken on National Trust land identifies what are believed to be two Roman villas

The largest geophysical survey ever commissioned by the National Trust has been undertaken at the Attingham Estate in Shropshire.

Historic engraving inspires Baroque parterre at Dyrham Park, one of the most notable stately homes of its age

An early 18th-century engraving has been used to create a striking new garden parterre at the National Trust’s Dyrham Park, one of the most notable stately homes of its age.

A soaring success for ancient insects - Wicken Fen announced as new Dragonfly Hotspot

Wicken Fen National Nature Reserve in Cambridgeshire, cared for by the National Trust, has been designated the UK’s newest dragonfly hotspot by the British Dragonfly Society. The title recognises years of conservation efforts to create ideal conditions for the ancient, winged insects to thrive.

National Trust unveils plans to double the size of Plymouth country park for city residents to enjoy

The National Trust has announced plans to open up more of its estate to double the size of the free-to-access country park at Saltram in Plymouth. The new area of country park will enhance public access, restore historical landscapes, and improve the area’s natural habitats.

Celebrated Mount Stewart garden wins European Garden Award for ‘exemplary’ climate mitigation measures

The National Trust’s Mount Stewart in County Down has received a first prize for Climate Mitigation Measures in Parks or Gardens in the European Garden Award.

Over 60,000 people march to parliament to demand politicians Restore Nature Now

On Saturday 22 June over 60,000 people marched through central London to parliament to send one simple but powerful message to all the UK’s political parties – that they must Restore Nature Now.

WaterAid Garden set to flourish in new home at the National Trust’s Manchester ‘sky park’ after winning Gold at RHS Chelsea Flower Show

WaterAid is delighted to announce the relocation of its striking Gold medal-winning garden from this year’s RHS Chelsea Flower Show to Castlefield Viaduct in Manchester, where it will inspire even more people to think about sustainable water management.

Hungry and hairy Hungarian hogs help save UK's most endangered butterfly

Conservationists racing to save the UK's most endangered butterfly have recruited the help of some unique volunteers: hairy Hungarian hogs.

Future plans for Castlefield Viaduct revealed and designs underway for extension

The National Trust has today revealed plans for the long-term future of the Castlefield Viaduct ‘sky park’ in Manchester. The masterplan, termed the ‘Vision,’ is a direct response to public feedback from viaduct visitors and the local community who took part in a series of workshops, events and an online survey in autumn 2023.

See-sawing fortunes for seabirds on the Farne Islands as puffin count gets underway

For the first time since 2019, rangers on the Farne Islands off the Northumberland coast, cared for by the National Trust, are gearing up to carry out a full puffin census, surveying eight of the 28 islands to get a vitally needed and critically overdue picture of the red-listed seabird’s numbers.

A memorial art installation to soldiers killed in the D-Day landing is coming to Stowe Gardens

A memorial installation to soldiers killed in the D-Day landing on 6 June 1944 will be coming to the UK for exhibition in September where it can be seen in full for the first time.

Lend a hand for nature with the Big Help Out 2024

The National Trust is marking the second Big Help Out Campaign with a range of activities from nature surveys, litter picks and beach cleans, to gardening.

Major European awards recognise conservation work of the National Trust

The conservation of a set of tapestries which took 24 years and cost £1.7 million to complete has won recognition from a major international heritage award.

King Charles confirmed as first recipient of Sycamore Gap seedling in honour of national Celebration Day

The first successful seedling nurtured from seeds collected from the 200-year-old Sycamore Gap tree after it was illegally felled by an act of vandalism last September has been gifted to His Majesty The King by the National Trust in honour of this year’s Celebration Day (Monday 27 May).

Beachgoers swap boogie boards for a boogie beach clean to help protect nature at popular Devon beach

The addition of a silent disco to beach cleans at the National Trust’s Woolacombe beach has seen numbers increase for vital conservation work to help protect nature.

Extinct plant reintroduced to the wild in Wales after 62 years

A beautiful mountain plant that once clung to cliff edges in Eryri (Snowdonia) has been successfully reintroduced in to the wild in Wales after being extinct since 1962.

The Octavia Hill Garden by Blue Diamond with the National Trust wins coveted People’s Choice Award – its third award of the week – at RHS Chelsea Flower Show

The Octavia Hill Garden by Blue Diamond with the National Trust has been awarded The People’s Choice Award at the RHS Chelsea Flower Show 2024.

Nature just the tonic for gin-clear ‘globally rare’ chalk stream in the Norfolk Broads

A project to revive a stretch of precious chalk stream in Norfolk that inspired poets and painters has been completed, marking the culmination of six-years of work led by the National Trust.

Borrowdale rainforest to become a new National Nature Reserve

On Wednesday 22 May, Borrowdale has been announced as the latest in the ‘King’s Series of National Nature Reserves’ (NNRs) by the National Trust and Natural England.

“Let’s aspire to fantastic urban spaces”: garden of ‘outdoor sitting rooms’ celebrating social pioneer Octavia Hill wins Silver-Gilt and inaugural RHS Children’s Choice Award at RHS Chelsea Flower show

The Octavia Hill Garden by Blue Diamond with the National Trust has been awarded a Silver-Gilt Medal at the RHS Chelsea Flower Show 2024.

Dame Judi Dench and school competition winner place Sycamore Gap seedling in The Octavia Hill Garden at Chelsea Flower Show

A seedling, grown from seeds collected from the Sycamore Gap tree after it was felled last September, has been placed in The Octavia Hill Garden at the Chelsea Flower Show by Dame Judi Dench and competition winner, 7-year-old Charlotte Crowe.

Charities back UK workers saying nature must be at the heart of business decisions

Three of the UK’s largest conservation charities are calling on companies to put nature at the heart of all business decisions.

New project is improving representation in the outdoors by training 100 new walk leaders from global majority communities

A new project that aims to improve representation in the outdoors by supporting people from the global majority to become qualified walk leaders has seen 24 participants successfully complete their first stage of training.

No shrinking violets! Conservation charity aims to create purple patch with mass planting of 20,000 violets to satisfy particular tastes of rare butterfly

Across the Shropshire Hills this spring, the National Trust and many dedicated volunteers will start the mass planting of 20,000 marsh violets, the largest planting of its kind in the UK.

His Majesty The King to continue royal patronage of the National Trust

His Majesty The King will be continuing his royal patronage of the National Trust, acting as the charity’s Patron.

Peatland restoration at Kinder Scout will plant 800,000 tiny ‘speed-bumps’ to improve health of the peatlands

Work has started to restore a new 526-hectare (1,300 acre) area of peatland on Kinder Scout in Derbyshire, the site of the famous mass trespass of 1932 that is now cared for by the National Trust.

Rare art work by 18th Century inventor of colour printing discovered at historic house in Norfolk

A rare surviving work by the inventor of colour printing discovered at Oxburgh Estate in Norfolk

Wicken Fen marks landmark 125th anniversary by announcing restoration plans to help ensure rare fenland endures for generations to come

The National Trust is marking 125 years of caring for one of the oldest nature reserves in the UK – and the very first it acquired - with the announcement of a £1.8 million project to restore 215 hectares (531 acres) of precious peat at Wicken Fen, making it the conservation charities largest lowland peat restoration project.

Partnership project to restore rivers in the Lake District wins 2024 UK River Prize

The Ullswater Catchment Management partnership, which is spearheaded by the National Trust and Ullswater Catchment Management Community Interest Company (UCMCIC) and works to restore and improve rivers in the Ullswater catchment in the Lake District, has won the prestigious 2024 UK River Prize’s Catchment Award.

Ghost of ‘lost’ blossom endures through street and place names, according to new research from the National Trust

With the National Trust’s Blossom Week about to bloom (20-28th April), new research published by the charity has revealed the significance of historic blossom in all its different guises in influencing the street and place names that still exist today.

New portrait – the first in over 100 years – joins unmatched collection of historic staff portraits at National Trust’s Erddig estate

For nearly 200 years, the cherished household staff and servants at Erddig near Wrexham were recorded in a unique collection of portraits, photographs and verses. Now, for the first time in more than a century, a new portrait is temporarily joining the historic display to mark the retirement of the estate’s long-serving Head Gardener.

Nature’s Confetti – Londoners invited to enjoy the spectacle of blossom in the heart of the capital at Outernet London

A new blossom experience – Nature’s Confetti - is blooming at the London’s Outernet as the National Trust aims to bring the beauty of this special moment in nature’s calendar to more Londoners, commuters and visitors to the capital.

Children's Urgent Call: More Time in Nature Essential Shows New Survey by National Trust and First News

Children want more time in nature and parents are calling on the government to achieve its goal of providing access to green space within a 15 minute walk, a new survey by First News and the National Trust shows.

Nature recovery on the Lizard is working from the ground up

Down on the Lizard, in deepest Cornwall, a landscape-scale coastal project to recover rare species is starting from the ground up.

18th century letters from a young man in London to his father in the Lake District reveal the expense, anxieties, and pleasures of life in the city

Three hundred years after they were written, letters from a son in London to his father in the historic county of Westmorland are going on display at the family home, revealing money worries, romances, nights out and work challenges that many today might recognise.

Visitors welcomed back on the Farne Islands

Inner Farne, one of the Farne Islands cared for by the National Trust, has reopened today for visitor boat landings, after a period of closure due to Avian Influenza.

National Trust's blossom campaign blooms with a feast for the senses on World Poetry Day

Marking World Poetry Day, the National Trust is officially launching its annual blossom campaign with the publication of a new book of blossom-inspired poetry by Poet Laureate Simon Armitage and the release of a new EP by his band LYR, both called Blossomise, inviting people in the UK to go out and immerse themselves in this year’s spring spectacle with each of their senses.

Series 8 of the award-winning National Trust Podcast launches on 4 April 2024

Daring 1930s heritage gangsters, pocket-sized urban gardens and an unsolved historical Whodunnit among the topics explored in the new series.

Meeting the bees needs - 50,000 unusual residents protected during National Trust Cymru repairs to historic house

For the first time in 200 years the buzz in a National Trust house in Gwynedd, North Wales has been stilled, as a rare species of wild bees living in the roof have been moved to a new home during conservation work.

Good news for historic collections as National Trust reports 18% tumble in clothes moths, but intense rainfall helps silverfish thrive

Clothes moth numbers tumbled in historic houses last year, the National Trust’s annual insect pests report has found. The report collates information gathered by house staff around the Trust, helping the charity to safeguard more than 1 million collection objects, from precious books and tapestries to silk hangings on state beds.

Seeds collected from felled Sycamore Gap tree ‘springing into life’ at specialist conservation centre

Seeds and material collected from the Sycamore Gap tree after it was felled last September are beginning to ‘spring into life’, according to conservationists at the National Trust.

Conservation of rare full-length portrait of an 18th century servant reveals tantalising clues about his identity and role

A rare full-length, life-size portrait of a servant at the National Trust’s Chirk Castle in Wrexham has gone on display following conservation and research to reveal some remarkable clues about his background.

Mild and wet weather results in early arrival of blossom in pockets of England and Wales

With February likely to be confirmed as the warmest on record, the unseasonably mild temperatures over the winter and wet weather of recent weeks have caused various flowering trees and blossom to emerge four weeks earlier than usual, according to gardeners at the National Trust.

Masterpiece Jacobean plasterwork ceiling depicting the Book of Genesis to get a new lease of life after 400 years

For the first time in its 400-year history, one of Europe’s most spectacular historic ceilings, depicting dozens of Biblical scenes, birds, and mythical beasts, is undergoing full conservation and repair.

Rare Roman head of Mercury discovered during dig at site of medieval Kent shipyard

The excavation in Kent of a medieval site that was once used for shipbuilding, has delighted archaeologists when they also came across earlier evidence of a Roman settlement.

New works supercharge precious peatland on England’s first ‘Super’ National Nature Reserve

Work to rewet and restore vital peatland habitats is underway on England’s first ‘super’ National Nature Reserve (NNR) in Purbeck, Dorset. The area was chosen as one of 16 sites for a £1 million Dorset Peat Partnership project seeking to reinstate 172 hectares (425 acres) of peatland, equivalent to the area of over 240 football pitches, across the county.

Visitors to be welcomed back on the Farne Islands

Inner Farne, one of the Farne Islands cared for by the National Trust, will re-open for visitor boat landings in the spring, after a period of closure due to Avian Influenza.

Rare watercolour from ‘The Jungle Book’ on display for first time at author’s family home Bateman’s, in the book’s anniversary year

A rare watercolour painting from ‘The Jungle Book’ is set to go on display at the book’s author’s family home, 130 years after the much-loved story was published.

National Trust issues key manifesto asks to protect nature and heritage for everyone

The National Trust’s Director-General Hilary McGrady has outlined the three minimum requirements any future Government should commit to, so the future of nature and heritage can be secured for everyone.

Statement on the felling of the Sycamore Gap Tree

Our statement on the sad felling of the Sycamore Gap Tree at Hadrian's Wall in Northumberland.

Response to Sycamore Gap tree felling “inspiring” says National Trust, as trunk to be moved from heritage site

The iconic Sycamore Gap tree is set to be moved from Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland, after it was felled in an act of vandalism a fortnight ago.

National Trust devotes record sum to historic buildings and collections conservation in 2022/23

The National Trust dedicated a record amount of funds to the conservation of historic buildings and collections in the last financial year, the charity’s latest Annual Report reveals.

Contact us

If you would like to see any further press releases from our archive please contact the press office.